The Story Behind the Book

Yet there is another type of revision, a re-vision, that is equally crucial. Every novel I’ve written has begun with a single image that I could not get out of my mind. In Saints at the River this image was a child’s face gazing up through water, in Serena a woman astride a huge white horse. The image that inspires my novel is always included in the final version, though sometimes it may be two pages or two hundred before it appears, and, because I never have an outline or conclusion, after a year or so I always reach a point where the novel stalls. Something important to the story is missing, I know, but just what that is I do not know.

There are certain lies that writers tell themselves to keep going, and one I make myself believe is akin to what Michelangelo believed about the uncut block of marble. The completed statue is already inside, waiting; it is only a matter of finding it. I make myself believe that since the initial image has imprinted itself so deeply in me, deep enough that I’ve spent a year of my life writing in response to that image, that the completed novel already exists. All I have to do is allow the story to reveal itself. This can take weeks or over a year, but there always comes a moment–and it is a moment—when the missing part comes clear.

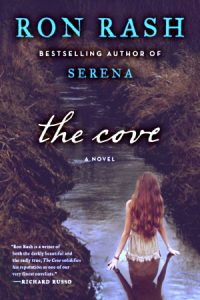

THE COVE began with the image of a young woman peering through the branches of a rhododendron bush and seeing a bedraggled man playing a beautiful silver flute. The image arose from research I had done, so I knew the year was 1918 and that the man was a fugitive. After a year, the novel flatlined, and for almost another year I could find no way to resuscitate it. Four more times I abandoned the story as a lost cause, but each time, after a couple of weeks, I went back to it. Finally, two years in, I realized what was wrong—the novel was ultimately Laurel’s story, not Walter’s. Furthermore, Chauncey Feith, who’d been a minor figure, became a major character. Only then did the story come alive. I cut a hundred pages and added fifty more. The novel I had been waiting for finally, finally emerged.