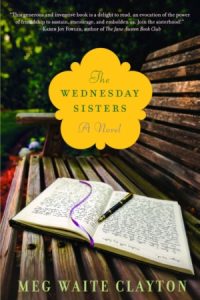

Story Behind the Book

The story itself started more than a year later, with a single nameless, faceless, character, just a character trait, really: white gloves—without any idea who wore them or why she might be a “Wednesday Sister.” But even before that, there was an ending to a children’s story I’ve never written, about a child who, like my own son, has a scar across the top of his head. There was a line in a Christmas letter from a friend of my mom’s, about the mysterious corner house in our old neighborhood that sat empty twenty years after we’d all moved away. There were the Hutchins Hall photographs of the nearly womanless Michigan Law School classes that came frighteningly few years before my own law school days. And another law school photo, me sitting on our balcony after my last second-year final, raising a wine glass to Jenn, who poured it for me and who is not hesitating to capture me at my worst on film.

My first journal entry for “The Wednesday Sisters”—the day after the white gloves attached themselves to the title without explaining themselves—begins: “Feeling incredibly well-run-dry today … I don’t have anything … Not a character yet. Not any idea where it will go, or even where it will start.” Which makes me laugh every time I read it, because a minute later a woman with a long blond braid sticking out of her Stanford cap walked across the patio where I sat, and though she was gone in seconds, pushed through the door to buy coffee or a Subway sandwich, I suppose (I never even saw her face), already that braid was not a real braid in my mind, and the character who would be Linda was bearing down on me, wondering if I could possibly get her story into words before it was lost. By the time I looked up a second time, I had the guts of Linda’s story—and of Kath’s, Ally’s, Frankie’s and Brett’s. I had the idea for the first paragraph, which turns out to be two paragraphs, and the last line of them. And I knew the story would be about their friendship, about getting each other through the bad times, and celebrating the good.

To be honest, Linda was wearing Brett’s white gloves at first, and the ending for the children’s story I’d never written, which was now the ending to her story, involved her husband rather than her friends. Frankie, who was named Bernie at first, wrote, but I wasn’t even imagining anyone else would, and though none of the five friends was much older than I was, those few years made a world of difference: they came of age and were married with children when the women’s movement began, while I came of age just on the other side, when women could apply to Harvard and Yale even if we couldn’t run Olympic marathons yet and didn’t sit on the Supreme Court. It’s something that has fascinated me since the day I saw the photographs of those nearly womenless law school classes, something I knew from very early on that I wanted to explore in this novel: how the women’s movement changed the world even for women of my mom’s generation who were committed to what is now called “the mommy track” before there was much of any other track at all. As was another issue the women’s movement addressed, one on which progress is still thin: the ideal of womanhood as Virgin Mary perfection that no real person can live up to. From the beginning, all the Wednesday Sisters loved to watch Miss America be crowned.

I’d like to pin the Wednesday Sister’s shortcomings on someone else, but the truth is they all represent some aspect of me. Linda’s fear—for her children and for herself—is definitely my fear: my mom is a breast cancer survivor; my grandmother did not survive. Brett’s tortured relationship with her “unfeminine intellect” draws its emotional roots from my own discomfort as a girl who was talented at math when girls weren’t supposed to be. Kath’s darkest moments draw from a relationship of mine that had not ended well. Frankie’s self-doubt and her chubby phases are mine, as is her experience with her first novel. Even Ally—whose story was inspired by that Christmas letter line about our old neighbor—is me in her middle-of-the-night journey back to the neonatal intensive care unit, where her daughter Hope is tethered to life by the same tubes and wires my own son once was.

The heart of the story, though? True, my friend Jenn doesn’t write. My friend Brenda does, but she’s quick to point out that she’s a Tuesday Sister, which was the day our writing group in Nashville met, and she swears she wouldn’t ever do what the Wednesday Sisters did for Linda, not even for me. My husband Mac, also a part of that Tuesday group, would, and he was very Linda-like in his pushing me to write, too, but he is … well … male. “Two Wednesday Sisters and one Husband”? Not such a good title, right? But the story behind the “The Wednesday Sisters” is those “Wednesday Sisters” of mine. It’s meant to be a hallelujah to them.