Q & A

A Conversation with Author Meg Waite Clayton

Q: While this novel is a work of fiction, you wrote about one of the household names in world literature, Ernest Hemingway, and narrated through the eyes of his third wife Martha Gellhorn, a lifelong journalist, war correspondent, and author. What was your motivation and inspiration for writing about Martha, and what do you want readers to take away from her story?

A: Like every other poor high school English student in this country, I slogged through The Old Man and the Sea long before I’d ever heard of The Trouble I’ve Seen or A Stricken Field. But I came to this story through Martha Gellhorn: I read about how she became one of the only journalists to go ashore in the early moments of the Normandy invasion, and I was hooked.

The Reader’s Digest condensed version of that story would go something like this: Denied an official opportunity to go across with the D-Day landing ships because she was female, Marty hid in the loo of the first hospital ship to cross the channel and went ashore with a stretcher crew to cover the landing in a brilliant article for Collier’s. As reward for her bravery, she was taken into custody, stripped of her press credential, and confined to a nurses’ training camp. But Marty, being Marty, hopped the fence and hitched a ride on a plane headed to Italy, where she continued do some of the best reporting to come out of the war even without her credential or any official support.

Really, how can you not want to know more about how Marty became Marty?

So began an obsession for me. When I heard Caroline Moorehead’s Martha Gellhorn: A Life, was to be published in October of 2003, I dug around to find a prepublication copy, which has long been underlined and dog-eared and loved to bits. I read her books, her articles, her letters. I wrote her estate executor in England to request access to her archives in Boston (denied), and petitioned the State Department for permission to visit Cuba in the days when that path was still largely closed (also denied, ah well). I visited places she’d been and tried to imagine being her, tried to learn everything I could. I discovered, among other things, that that first version of the D-Day story was a bit of an exaggeration: she didn’t hop that fence; she rolled under it.

I also discovered that she had been the lead correspondent for Collier’s until a man snagged the position from her—and that man was her husband, Ernest Hemingway.

For me, a novel is a long part of my life, all-consuming often for years. I can’t write a book “to order,” and don’t want to. As Marty writes in an August 1940 letter to Charles Scribner, in explanation for why she is turning down a contract to write a book for Scribner’s, “I could not do a book (a book, Charlie, think of the high pile of bare white paper that you have in front of you before there is even the beginning of a book), unless I believed awfully hard in it. Unless I wanted to do it so much that I could sweat through the dissatisfaction and weariness and failure and all the rest you have to sweat through.”

I’ve been mopping the sweat from this one for a long time. My hope for what began as one of those high piles of white paper is that it will introduce others to the truly extraordinary Martha Gellhorn.

Q: It is obvious that you conducted extensive research for this novel on both Gellhorn and Hemingway; in the Author’s Note you mention referring to biographies, articles, published letters, and of course the two authors’ own writings. What was your approach to staying true to history while maintaining creative license? Are there any parts of the book that readers would be surprised are based in fact, not fiction?

A: I know not all authors are with me on this, but I feel if I am dealing with real people, I ought to honor their lives as they were lived. To intentionally make up stories about real people seems to me to lean on the crutch of a famous name in service of a story that ought to be able to stand on its own. And … let’s just say I can’t imagine portraying Ernest Hemingway stripped to his long johns, with a cleaning bucket on his head and brandishing a mop, if I didn’t have a basis in fact for it.

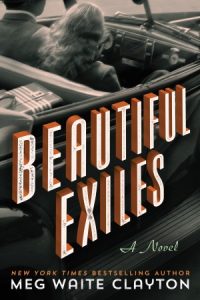

As might be expected for a story that begins with one clandestine relationship and ends with another—and involving people as famous as Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway—the many sources I turned to in the writing of Beautiful Exiles often differed on even the simplest of things, including who was where when. I sorted through those discrepancies as best I could, with the intent of being as true to the facts of their relationship as possible. I can’t think of a scene in the book that isn’t grounded in fact.

Q: As the novel progresses and their career aspirations pull them in different directions, Gellhorn and Hemingway struggle to find a path that works for each of them and for their relationship. As they are courting, even Martha’s mother questions whether Martha ought to marry Ernest. How do you think this novel addresses the theme of independence and identity, especially with respect to how Martha evolves during her relationship with Ernest?

A: This question—how one keeps identity and independence when involved with such a larger-than-life lover—is the thing that drew me most to focus on this particular part of Martha’s life. Even now, when women are no longer expected to abandon their dreams to support their husbands, the weight of the career-home balance tilts heavily to the female side of the scale. And where ambition is admired in men, it remains suspect in women.

So she’s ambitious. He’s ambitious. Things go well when their ambitions align, less so when they do not. I think the way Ernest so often deferred to Marty’s ambitions in their early years together is a testament to his love for her—and I do think Marty was the love of his life.

I give a lot of credit to Martha, though. She’s pretty good at insisting on a relationship based on something closer to equality than Ernest had with other women. Not that she thinks herself Ernest’s literary equal. What she loves about him is his outsized writing ability, and his generosity in supporting her, in teaching her. She’s actually a better war reporter than he is, although she doesn’t even imagine herself that. But she does recognize that for their relationship to work—for any relationship to work for her—she needs to hang on to her own identity. She writes Hemingway from England during World War II, when he is still back in Cuba and wants her to come home, “I have to live my way as well as yours, or there wouldn’t be any me to love you with.”

She also writes at one point, “The only way I can pay back for what fate and society have handed me is to try, in minor totally useless ways, to make an angry sound against injustice.” Even before she meets Ernest, she has spent time in Europe and is horrified at the rise of Hitler and fascism, and she’s intent on making that angry sound. She is sincere in this, but it is also has the benefit of being the easy path for an ambitious woman of her time to hold on to (and ours, for that matter)—one that suggests just the kind of self-sacrifice we expect of women.

So most of their life together is spent taking turns, or going their separate ways and coming back together. He leaves Spain for France because Collier’s sends her to cover the looming threat of war in France. She stays in Cuba so he can finish For Whom the Bell Tolls. She covers Prague while he returns to Spain. She goes to Sweden while he stays in Idaho with his sons. They “honeymoon” in China, where she covers the Sino-Japanese war. It’s the only scenario, I think, in which their relationship can survive. When and how and why it succeeds and doesn’t is complicated—complicated enough for me, at least, that it took me the writing of an entire novel to understand.

Q: Gellhorn came into her professional own during a time when women journalists weren’t given the support or respect they deserved. That great story about her literally skirting a fence to get out of the nurses’ compound where military officials had her staying since she was a female, not male, war reporter. How did Gellhorn’s early work, her grit and determination, impact the future of journalism and reporting for women in the field?

A: Marty was not the first woman to cover war; as early as 1848, Margaret Fuller was covering an uprising in Italy for the New York Tribune, and when Martha set off for France in 1930, determined to become a foreign correspondent, Sigrid Schultz was in her fifth year as the Chicago Tribune’s bureau chief in Berlin, where Dorothy Thompson would interview Hitler the following year.

But there is a bit of a pivot in the progress of women journalists that really comes in the days between D-Day in June of 1944 and the liberation of Paris later that summer. Before the liberation of Paris, women journalists were officially forbidden to cover the front. But starting with that moment Martha stows away in that hospital ship to cross the channel, women journalists begin to see that to cover the front they are going to have to go AWOL from support positions to get to the actual war, climb fences meant to contain them, and risk their lives. Despite being confronted with red tape and derision, denied accommodations provided to their male colleagues at press camps, pursued by military police, and even arrested and stripped of credentials, women like Martha—and others including Lee Carson, Helen Kirkpatrick, Iris Carpenter, Ruth Cowan, and Lee Miller—proved that women could report the war, and do a damned good job of it. They did such a good job that, beginning that fall, the powers that be began to accredit women journalists to the front—opening up the future for generations of women journalists.

Q: Travel and experiencing things firsthand are the main drivers of both Gellhorn’s and Hemingway’s writing, but they are also what ultimately drives the couple apart: Martha constantly itches to return to Europe, while Ernest becomes content to aid the war effort on his boat off the Cuban coast. How has travel influenced your own writing? Did you travel at all as part of writing this novel?

A: I am answering this from Paris, on a three-month, twelve-city adventure. I’ve seen attributed to Marty the quote “travel is compost for the mind” and while I haven’t been able to source the exact quote, it is a pretty accurate distillation of some longer passages in her letters, and I completely agree. Like Martha, I find going off the map, or off my familiar map, sends my mind in different directions, questioning things that at home would go unquestioned, and that is where some of my best writing comes from. I did travel as part of writing this novel—to Key West, to Paris, to Prague and elsewhere. I sometimes wonder if I write to travel, or if I travel to write.

Q: On your website, you say: “If I had to pick a single word to describe what makes me a writer, it would be discipline.” You portray Hemingway to have a similar sense of discipline, as he sits down for hours or even days at a time to get his ideas punched into his typewriter. Gellhorn, on the other hand, seems less regimented, writing much more freely in the thick of war-torn Spain or France than she does at home in Cuba. How do you think their approaches to writing speaks to differences in their character? Do you feel you identify with one of them more than the other, based on the method in which you write?

A: There is a very funny passage in a February 24, 1940 letter from Ernest to his publisher, Charles Scribner, in which Hemingway explains to Charlie—who, having gotten wind of the fact that Hemingway counts his words every day, worries his best writer is going batty. Ernest writes, “Don’t worry about the words. I’ve been doing that since 1921. I always count them when I knock off and am drinking the first whiskey and soda. Guess I got in the habit writing dispatches.” And in another, a September 3, 1930 letter to his editor, Max Perkins, he writes, “I have to stick to one thing when I’m writing a book and keep that in my head and nothing else.”

I completely identify with him on this, although perhaps with a little less whiskey in the mix. Writing-habit-wise, I’m far more Hemingwayesque, right down to the word counting. When I am writing first draft, my rule is 2,000 words or 2:00. If I’ve written 2,000 words by 9 a.m., I can turn on the tellie and pull out the bon-bons. But actually, if I have 2,000 words by 9 a.m., Mac has to come haul me out of my chair for dinner, because that is a great writing day.

It did make me feel a little saner to read that Hemingway counted words, and weighed himself each morning, as I also do, although I would never display my weight on a wall.

But hmmm… Perhaps it should leave me more worried about my sanity?

Q: The novel’s title, Beautiful Exiles, can be interpreted in a lot of different ways. What sentiment were you hoping to capture in this title?

A: I have to say choosing a title for a book, at least for me, is more feel than logic, so take what follows here with that in mind.

The working title for this book was “Mookie & Bug”—two of the nicknames Marty and Ernest called each other—but my agent felt that title suggested a young adult novel, which this is decidedly not. But retitling a finished manuscript is a bit like renaming a fully-grown child just as she is submitting her college applications. I love the new title, but one part of me will always think of this novel as “Mookie & Bug.”

At some point we’d settled on a title with “wife” in it, to be honest probably because some books with “wife” in the title were doing well, and I’d done pretty well with “sisters.” But I secretly hated the wife titles; it was the one thing Martha dreaded, to be identified as “wife,” and I felt I was doing her an injustice. So I just stepped back and made a list of titles or even just words—anything that came to mind. Unfiltered. Unedited. In the privacy of my little office, where I would write my weight on the wall if I wrote it anywhere, which I never would.

One of those words was “exile.”

Trying to parse it logically, I suppose Marty was a bit of an exile on her own, exiled by the expectations that came with being from a prominent St. Louis family, and by her complicated relationship with her father. But the word also felt right because Marty and Ernest together are essentially exiled by his fame. When they are first falling in love, he is already famous enough that in the U.S. they would be hounded by photographers. How can you possibly sort out a relationship in that glare? They go to Cuba for the privacy it affords them to sort out whether they even really want a relationship.

So I took “exiles” and I did what Hemingway often did for titles: I turned to the bible and poetry, searching for some nice poetic title with the word “exile” in it. The best I could come up with was “Sojourners and Exiles.” (“Beloved, I urge you as sojourners and exiles to abstain from the passions of the flesh, which wage war against your soul.” 1 Peter 2:11.) But yeah, “sojourners.” Hard to use that one in these post-Biblical times without evoking Sojourner Truth who does not, I must tell you, appear anywhere in these pages.

The thing about Ernest and Marty’s exile is that in many ways, for many years, it worked for them. They did have the privacy to sort out how they felt about each other outside the glare of the press, for the most part. And the place they created together—the Finca Vigía—is really beautiful.

And then they were a beautiful couple, and beautiful writers. In the end and despite everything, I don’t think either of them ever loved anyone more. Their relationship was stormy, but I think their best work—for both of them—came out of their years together.

So “beautiful”—I liked the double meaning: they are beautiful exiles, and their exile together allowed them to write beautifully, the kind of writing that they both wanted more than anything else.