Library Journal Feature

Library Journal — March 15, 2007

Books by Camel: A Heartfelt but Tricky Business

By Barbara Hoffert

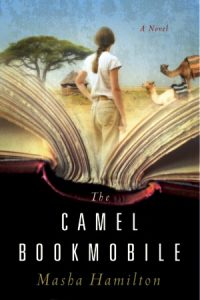

Behind the Book: Masha Hamilton’s The Camel Bookmobile.

A journalist who has worked worldwide and the author of two other novels (including The Distance Between Us, an LJ Best Book), Hamilton got the idea for her Kenyan saga while driving to the Kirk-Bear Canyon Branch Library, Pima County P.L., AZ, with her three children. Her daughter was reading about Kenya’s book-bearing camels in Time for Kids magazine, and as she enthusiastically shared her findings, “the story came to me in a flash,” reports Hamilton. Initially, she envisioned a child badly injured by a hyena, and he remains in the book as Scar Boy, an outcast whose life is transformed by the camel bookmobile in unexpected ways. But the bookmobile would not be possible without committed librarians, and thus was born starry-eyed Fiona Sweeney, fresh from New York City.

Like all of the book’s characters, Fiona comes strictly from Hamilton’s imagination. “When I write, the characters make themselves known,” she reveals. “It’s like sitting next to someone at the airport.” Not that she hopped on the first flight to Kenya to get a feel for the country before crafting her tale. Instead, she used those finely honed journalist skills to do the necessary research. “I wanted that information to impact me greatly,” she says of her reading and relentless emailing, “but I wanted the story to develop before I saw the place.

“In fact, Hamilton did not visit Kenya until her book was signed by HarperCollins. Accompanied by her daughter, she sallied forth with the mobile library service and had an extraordinary sense of rightness. “It was exactly as I described, with fences built out of blown weeds,” she says happily. “I told one of the librarians he could almost be Mr. Abasi”—the curmudgeonly director of the book’s camel-driven service, who has doubts about its worth.

Culture clash, shared humanity

Yet as one character complains, “The library is from another world. A world that does not serve us.” Beloved by some villagers, who are as eloquent as Fiona in celebrating the value of reading, the bookmobile is seen by others as a terrible threat to the life they’ve known forever. Hamilton has always been concerned with cultural differences—her previous novels were set in the Middle East—and here she shows the disruption that can arrive with the dust stirred by the camels. But Fiona remains oblivious. Observes Hamilton, “Even when we have the best of intentions, our lack of understanding of other cultures can cause problems.”

Throughout, though, The Camel Bookmobile also reveals our shared humanity; one delight of the narrative is wandering amid the little settlement it depicts and encountering people with our very hopes and fears and sorrows. Though her fiction thus far has been set abroad, Hamilton argues that we can learn about ourselves by learning about others: “I see myself freshly through that foreign lens that is like me. When a friend asked, Why don’t you write about us?’ I said, ‘I do.'”

In the end, writing is something Hamilton does because “it’s how I understand myself and my world.” She’s been at it since age eight, and after many enjoyable years of overseas reporting, she finally decided to risk leaping into something more creative. “Journalism is great preparation for writing fiction,” she reasons, “because you let go of your ego and listen to others. But I really came to feel that in writing fiction there is a deeper truth.”

Since Kenya’s national library fixed on Camelus dromedarius as the ideal means of “nonmotorized transport” for book delivery, the Camel Mobile Library Service has thrived. But it’s not without its problems, from inadequate funding to indisposed camels. Of course, there is always a crying need for books—particularly scarce in the local languages, though English-language materials are also welcome—and Hamilton is pitching in by encouraging authors to donate their books (see camelbookdrive.wordpress.com). In addition, anyone interested in donating can send materials to Garissa Provincial Library, For Camel Library, Librarian in Charge, Rashid M. Farah, P.O. Box 245, Garissa, Kenya. Just think, anything you send will soon be on its way by camelback across Kenya’s umber landscape, ready to educate and enthrall people living on the margins who until recently may never have seen a book.

Barbara Hoffert is Editor, LJ Book Review