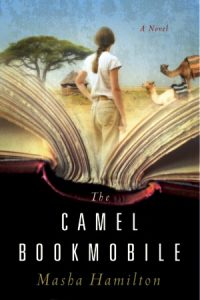

The Story Behind the Book

The Camel Bookmobile made its first run almost a decade ago. Three dromedaries trudged through dusty, arid northeastern Kenya near the border with Somalia to bring a library to settlements so tiny and far-flung they’d become nearly invisible; places lacking roads and schools, where most people had never held a book between their hands and where they lived daily with drought, hunger and disease.

The fine was intended both to protect books so literacy could spread, and to encourage a wandering people to adopt the practices of a more settled world. But reality, as always, would be more complex than theory, I knew.

As I listened, the entire arc of a story came to me in one gulp. I imagined an American librarian who travels to Africa to give meaning to her own life, and ends up losing a piece of her heart. I saw a scarred African boy, once mauled nearly to death by a hyena, who finds an extraordinary way to enlarge his narrow world. I saw a huddle of mud and dung huts where a few books go missing, and where people who fear for their way of life turn their anger on the disfigured boy.

Through it all, I envisioned books – Dr. Seuss, Homer, vegetarian cookbooks, Tom Sawyer, Hemingway novels, Zen meditations, short stories about modern love – traveling through the remote desert on the arched backs of camels, like notes from another world sealed in a bottle and tossed into a sea.

Why have my novels been set in foreign countries? I’ve been asked this question. I’ve been told Americans only like to read about themselves. But like Fi Sweeney, the librarian in the novel, I’m convinced that the chance to see ourselves through another’s prism is important – perhaps more than ever. One theme the novel explores that may be particularly crucial right now is the idea that American generosity, deeply rooted in our national character, can also sometimes inadvertently cause harm.

I had more to learn about the book’s characters and their world, of course, and bringing them to life on the page still took years after that initial swell of story. But because I knew so much of the story so quickly, I had company during the writing process. Fi Sweeney, Scar Boy, the village teacher Matani, his alluring wife Jwahir and her lover, the drummaker Abayomi: from the first, their voices joined together to narrate a tale I could not ignore.

(Pictures on this page show Masha with the actual camel-back library in Kenya during her trip in February 2006)