The Story Behind the Book

Whence Prague?

It was that kind of place then.

The diverse Westerners who moved to Budapest, Hungary after the fall of Communism shared one peculiar feature: they were buzzingly and weirdly conscious of their moment in History.

The tiniest little investment bank trainee, girdled with that most American of credentials, the MBA, spoke openly of a gold rush to the Wild, Wild East, of the virtuous democratizing power of investment, of capitalism’s recent empirical and inevitable triumph, as if History had just completed a 75-year, double-blind, controlled test with Capitalism trumping both Communism and the placebo.

Glowing young diplomats were wide-eyed and grinning, as they were clutching a forty-five-year-old lottery ticket the day Containment’s lucky number came up. Now they would witness and administer a new Marshall Plan, draft constitutions, hold the righteous pens indelibly redrawing the continental map.

Artists and would-be bohemians drowsily stepped off their Swissair flights and, that same night, in the smoke and din of a café, remarked on 1990 Budapest’s uncanny parallels to 1920s Paris. Soon The New York Times would confirm this (although, infuriatingly, they would use Bohemian Prague as the new bohemia instead). Even if you had no personality at all, or were still deciding among several, this was the place to be. Posing and dancing in all this History (real Soviet soldiers!) couldn’t help but give you some sort of allure.

Across the smoking footlights were smoking Hungarians, and how self-conscious were they? It was hard to tell. They were alien in alien ways. Many of them were staggeringly attractive and effortlessly sophisticated (the average Hungarian twenty-year-old could and would tell you why the Versailles Treaty was a clumsy provocation to irredentist hatred and warfare), but they dined unironically on goose drippings, and listened to bootleg tapes of the Bee Gee’s. They spoke a patently unlearnable tongue, enjoyed a national reputation for slippery resilience, and were only temporarily impressed by the foreigners’ escapades. Most importantly, every last Hungarian had lived through scathing events that most of the invading young Westerners had only read about or seen on television. This often inspired an odd, mutual envy.

As everyone’s shared proscenium, there was Budapest, this city. “Paris on the Danube,” boasted the concierges, the chronically misspelled tourist brochures, and the strutting new Anglophone newspapers. Pockmarked, dusty, unpainted, crumbling, still ringing with the echoes of echoes of gunshots from 1956 and 1944, she blithely radiated so much beauty—for those whose tastes bend this way—not just in the river and the hills and the dizzying twist of Baroque and Turkish and Second Empire and Stalinist architecture, but in the omnipresent decay, and in the tender last days of the visibly doomed: the black markets and wacky restaurants and genteel remnants that could not survive; the Communist associations clinging anachronistically to their high-end real estate for purposes idealistic or sinister or both; the passing generation that had groaned or prospered or compromised under ghastly or buffoonish tyrants; the fifteen-cent tickets to the Opera; the subway operating on the honor system; the factory workers living in the city’s most desirable district.

I wrote this book to exorcise (or just exercise) my obsessive love for this city (which no longer exists, I am told). In the end, I managed only to reproduce a shadow town, hovering (depending on the angle of the light) 3-5 km NE of the real Budapest, precariously set at a slightly higher altitude.

I wrote this book out of affection for my own past (although I surgically excised myself from the final product), and out of frustration with my congenital disorder, hyperglycemic nostalgia.

For some people I knew, the ear-popping pressure of so much history and self-consciousness made it hard to get up in the morning, to justify your lunch, let alone your existence. What does it mean to tell a girl you ache for her as the two of you stand in front of a building with bullet holes in it? What does it mean to fret about your fledgling and blatantly temporary career when the man next to you managed to get himself tortured by the secret police of two different regimes? How do you compare your short and uneventful life to the lives of those who actually rebelled, fought, died, sinned? Does the present owe a debt to the past? Will this place be remembered, and me with it? Maybe this would all feel more real if I were elsewhere… But who do I talk to about this, when the only language everyone seems to speak is cast-iron irony?

Prague makes absolutely no headway in answering these prickly questions, thank heaven.

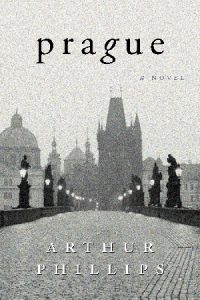

Why call a novel set in Budapest Prague? The Czech capital offered far more stunning architecture than its Hungarian neighbor, and got credit for hosting more important artists and better economic prospects than Budapest. To John Price, a young man who aspires to Life, but only leads a life, Prague glows—the place where Real Life carouses, a party where you were expected an hour ago while, hour after maddening hour, you can’t button your dreamily unwieldy shirt.

John Price is, I’m guessing, not the only one who suspects that the real action is still just ahead, in Prague, in the next city, the next job, the next beautiful stranger’s bed, or (far, far more troubling) that Life is unbearably, permanently out of reach, trapped in the amber of some heirloom era like 1920’s Paris. In Prague, the present limps to a sorry third-place finish, far behind the potential glories of the future and the fairytale splendor of the past. That the actual city of Prague resembles the lovely, ghostly setting of a dimly recalled and yearningly significant fairytale is no mean coincidence.

About the Author

Arthur Phillips was born in Minneapolis and educated at Harvard. He has been a child actor, a jazz musician, a speechwriter, a dismally failed entrepreneur, and a five-time Jeopardy! champion. He lived in Budapest from 1990 to 1992 and now lives in Paris with his wife and son.