The Story Behind the Book

When I told one of my oldest and dearest friends that I was writing a book about the Poor Clares, he threw up his hands in exasperation at my seemingly hopeless attraction to failure and snapped, “Who’s going to want to read about a bunch of old women who don’t have sex?” Despite reactions like that, I had an idea that there were other people like me- people whose lives were full of the arts and politics and family and friends and gardening and sea kayaking and yoga (okay, my life is only partly full of those things) but yearned for something bigger. Who wondered if there was a divine pulse behind it all, who wanted to touch it. One of these people, a friend who’s active in the arts and local feminism and runs a big nonprofit–no one would suspect her of any shameful yearning for faith!–was fascinated by my discussions with the Poor Clares. She had been feeling some of the same longings as I–and the same reservations, too. She confessed that she had been driving along in her car one day and was listening with interest to some sort of commentary on the radio, but when the announcer identified it as a religious station, she quickly changed the channel. How alarming to have found herself listening to such people!

I suppose writing a book, any book, changes you–you think about things and think about them and carry them around in your head for weeks. They carve new shapes in your mind. Among other changes, I seem to have emerged from writing this book with a new appreciation for stillness. As I sat in the Poor Clares’ big old monastery week after week, I grew to like the sounds of its silence all around me. I felt their tremendous striving in the silence and also their waiting-a form of striving, of holding themselves back from anything that might distract them from God. I was one of those distractions, and they put up with me graciously. And then it ended, when each had told me all she had to say about her path towards this extraordinary commitment, when each had answered my questions about prayer and spirit and a life of faith.

I only see them through the grates these days, same as everyone else–a rustle of brown cloth, a flash of white collar, the occasional gleam of a medallion. Once in a while, one of them will wave before they disappear into the cloister after mass. I can’t claim more of their time. They have so many prayers to say these days–it’s a wonder they haven’t fallen over, exhausted by the world’s explosive needs.

They’ve changed, too, since my weekly visits ended. The oldest of the nuns died, leaving fewer of the marathon prayer-makers there than ever. Three nuns from a Poor Clares monastery in Korea moved in. A few younger women have visited the cloister and tried on their life for a while, but I’m not sure if any of them have been willing to give up the outside world. It surprises me when there’s any sort of change behind the monastery’s heavy walls–it always seems that nothing changes there, that time passes at a different rate inside, that time matters less than it does on the world outside. Maybe it’s just that I like to think of the Poor Clares that way: that they will go on and on and on, throughout the days and nights, praying for all of us–even by name, if we ask them. The trees filling our skies with oxygen, the Poor Clares filling the skies with faith.

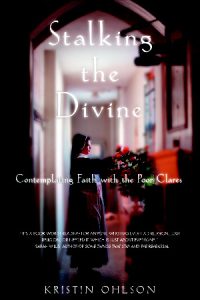

About the author

Kristin Ohlson is a freelance writer who has published nonfiction articles and essays in the New York Times, Ms, Salon, Discover, New Scientist, Food & Wine, Tin House, and many regional and alumni publications. She has also published short fiction in Ascent, Indiana Review, Akros and other literary magazines. She received a BA in English from Cleveland State University and an MFA from Bennington College. Born and raised in Oroville, California, she now lives in Cleveland, just miles from the Poor Clares.