The Story Behind the Book

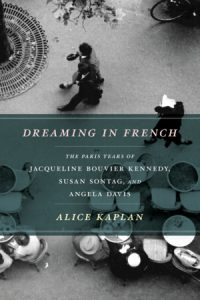

DREAMING IN FRENCH: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis by Alice Kaplan

Then there’s Sabrina, from the Billy Wilder movie “Sabrina,” after her course at the Cordon Bleu. She writes to her father from her garret in Montmartre: “I’ve learned so many things father. Not just how to make Vichyssois or calf’s head with sauce vinaigrette, but a much more important recipe. I have learned how to live, how to be in the world and of the world and not just to stand aside and watch. And I will never, never again run away from life, or from love either.”

But who are the real female heroes of study abroad? And isn’t there more to it than a cloche hat and a Givenchy suit? Those were the questions that started me on my search. I wanted to write about American women who had been transformed by a year of study in France and who had gone on to transform American life. It was clear from the beginning that the first woman in my book was going to be Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy. Probably because she had been my own escort into the French language, in 1965. I was in fifth grade, in a girls’ school in the Midwest, and we were all required to choose a French name by which we’d be addressed in class. It was the name we would use to sign all our homework papers and tests. When it came time for me to choose, I didn’t hesitate for a second: I was Jacqueline. At home, my brother had a yellow parakeet he’d named Jacqueline. Kennedy had been dead for a year and a half , we were marked by that loss, by the image of Jacqueline Kennedy in her black dress and veil at the grave, and so we named things after her. But there was nothing mournful about it: the elegant parakeet in her bright yellow coat was Jacqueline, and Jacqueline was what I wanted to be, too. Working on the real Jacqueline Bouvier was a way of coming full circle, of deconstructing my childhood fantasy. My work on Jacqueline Bouvier was the biggest surprise of the book–I expected to find a snob, I wondered if she had anything to say… and the more I learned about her, through her host sister Claude in Paris and her friends on the Smith College program, and through her own writing, the more I came to like and respect her. Her grandfather had invented a story about the family’s aristocratic French past;but she made of her very real relationship to France a rich intellectual and artistic life, a counter life that was a consolation for all the rest.

One of the great experiences I had working on “Dreaming in French” was meeting Martha Rusk, Jacqueline Bouvier’s best friend on the Smith Junior Year in 1949. Martha and I had corresponded for a few years, and by the time I met her she was very ill and knew she didn’t have long to live. Over lunch in her New York apartment, she shared her favorite story about Jacqueline on study abroad: Jacqueline in her red circle skirt and white shirt, traveling with a hat pin for overnight train rides, which she passed to her girlfriends, whenever someone tried to grope them. Martha told me about her trip with Jacqueline to Dachau, what it was like to tour the remains of the camp so soon after the liberation, and how stunned they were on the tramway back to Munich. She had stories too about the magnificent Mlle Saleil, the director of their program, a multi-talented professor who designed and sewed all the costumes for the 1940s Smith College production of “Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme” and who seemed to know every important writer and artist in Paris. Their time in a city close to the experience of war, so uncomfortable and foreign in many ways, had been their personal liberation. Paris made them the women they would become.