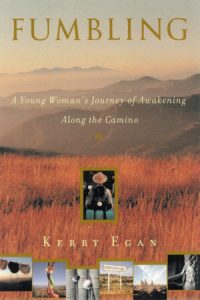

The Story Behind the Book

I became a pilgrim when I was twenty-five. Though it was a year after my father died, it was only as I walked through the fields of northern Spain on the medieval Catholic pilgrimage route of the Camino de Santiago, with Alex, my self-proclaimed protector, that I started to grieve. Grieving did not come quickly to me. I worked very hard for a year to hold it off, perhaps because to grieve is to admit that the past cannot be changed, and more than anything else in the world, that year, I wanted to change the past. Grief is not something you might think you have to learn, but I did, and I learned in a way that still surprises me, even as I write about it: I learned when I began to sense God all around me, in mud and slugs, in chickens in a gilded coop, in a man who truly believes he is the modern reincarnation of a Knight Templar, and most important, Alex’s love. I had never known to look in these places, and the God I found there I had not learned about either as a child or in Divinity School. This was a God I never knew to look for. This book is about learning to pray, which is learning to recognize God. This book is about faith in the face of grief.

The thread that runs through the book, that notions of prayer and ways of praying continue to expand as one opens up more and more to the reality of God, might not be immediately visible to the reader, just as the truth of this was not immediately visible to me as I walked. The theme of prayer as I define it-recognizing God in all things–unfolds as the narrative unfolds. The story that the reader sees and grasps from the outset is the adventure of walking a revived medieval pilgrimage through rural Spain and the parallel story of my long journey of coming to terms with my Dad’s death, an interior movement that began with a lot of screaming at Spanish wheat fields. The arc of the story of the journey-the people we met and the things we saw, the beginning of grief and the return to “regular” life-is reflected and shadowed by another arc-that of expanding notions of prayer and of God.

When I left for Spain, all I really wanted to know was how my life would turn out. I had seen up close how painful and even humiliating life could be, through my father. Some part of me conflated knowledge with control: if I could know what would happen to me, I could control it and therefore prevent pain. I wanted a map of my life, so I could know just where I was headed, so I prayed for one. If there is anything I learned being a pilgrim, it is that praying for a roadmap makes little sense. It makes much more sense to pray for strength to keep going and clarity to see where the road is turning. Mostly, though, the point of praying is simply to do it. It is enough just to spend time being aware of God, of keeping your eyes open for God.

God is completely different from anything I assumed or imagined. It is this intangible, ineffable quality of God that has led so many theologians into tangles of wordiness that strip the Divine of anything approaching wonder and so many mystics into the world of metaphor that can be alien to experiences most people ever have. I want to write in the middle ground-I want to write a “narrative theology.”

Narrative theology is lucid and concrete about what prayer can be; at the same time it brings the reader into the sensual, emotional, and mysterious experience of God. I want to do theology without the wordiness, and mysticism without the abstraction.

My version of narrative theology combines some of the insights of the study of religion with my experience of being a pilgrim without separating the reader and the writer from the experience, as traditional theology and comparative religion sometimes do, or ignoring the illumination and revelation that can come through studying and learning from the work of others, as some spiritual writing does. The immediate and sensory experiences of pilgrimage that I share with the reader are enriched and expanded by the insights of comparative religion, history, and theology, at the same time that theology and religious studies are given breath by individual encounter with God. The story remains foremost, engaging and enveloping the reader, but the theory informs the way I tell the story and context I give it.

The theory and history I share with the reader is not separated from the story itself. It is a part of the story because it is a part of me. I was a pilgrim, but I was also a student at Harvard Divinity School at the same time. The spiritual and emotional can coincide with the rational and academic in the story, because they coincide in me. In the end, though, the theme of prayer and the story of the journey merge, just as the theological and experiential merge, as walking and grieving became prayer. When I learned to pray, I was able to start to grieve.

That all things can and should be prayer is not a radical and new idea. It is a very old idea that many theologians have written about, but it is often difficult for readers to understand how to make sense of this idea when described abstractly. I want to describe this idea and argue this point not through the traditional style of theology, but by telling a story, because I think that is how people really communicate ideas and concepts to each other.

At some point, theory falls apart. At moments of greatest joy and greatest despair, emotions transcend anything explicable. Most often, a person who has just lost a wife, or a son, or a mother, or a lover will tell me, his chaplain, stories about the person who is lying dead in front of us. Through these stories the teller finds meaning, not through any grand theory. Because I am his chaplain, I sit with the bereaved, letting him know that he is not alone, that he can reach to joy and wonder, and sink low into sadness and pain, and he will not be alone and these things will not destroy him; he will not implode with the power of what he is feeling and I will not distance myself from him.

With the book, the reader can accompany me in my story, if she wants, to the very low and painful places and to the very joyful and wonder filled places, and I will stay with her. I promise the reader I won’t distance myself from her by analyzing; I won’t try to explain what happened away. I’ll let the story do the work and let the narrative carry the meaning…

About the author

Kerry Egan was born and grew up on Long Island, New York. She received her B.A. from Washington and lee University, graduating magna cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, University Scholar and with honors in religion before attending Harvard University Divinity School. While at Harvard, she worked at various times as a nursing home ombudsman, a chaplain intern at Dana Farber Cancer Institute, and a research assistant for Lawrence Sullivan, director of Harvard University’s Center for the Study of World Religions. She graduated from HDS in June 2001 with a Master’s of Divinity.