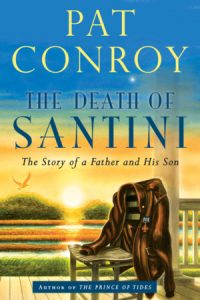

Reviews

Review Excerpts

New York Times Book Review – November 17, 2013

“Conroy announces that the fictions he has spun over his long, celebrated literary career aren’t really fictions. They’re diamonds hauled up to earth and into the light of day from the dark and bottomless mine of his Southern clan. Conroy tends to paint in extravagant strokes and SANTINNI instantly reminded me of the decadent pleasures of his language, of his promiscuous gift for metaphor and of his ability, in the finest passages of his fiction, to make the love, hurt or terror a protagonist feels seem to be the only emotion the world could possibly have room for, the rightful center of the trembling universe.”

The Boston Globe – October 26, 2013

“Conroy remains a brilliant storyteller, a master of sarcasm, and a hallucinatory stylist whose obsession with the impress of the past on the present binds him to Southern literary tradition…”

Washington Post – October 25, 2013

“…Conroy has fashioned a memoir that is vital, large-hearted and often raucously funny. The result is an act of hard-won forgiveness, a deeply considered meditation on the impossibly complex nature of families and a valuable contribution to the literature of fathers and sons…”

Kirkus Starred Review – October 1, 2013

“An emotionally difficult journey that should lend fans of Conroy’s fiction an insightful back story to his richly imagined characters. One of the most widely read authors from the American South puts his demons to bed at long last. One doesn’t have to have read The Great Santini to know that Pat Conroy was deeply scarred by his childhood. It is the theme of his work and his life, from the love-hate relationship in The Lords of Discipline to broken Tom Wingo in The Prince of Tides to the mourning survivor Jack McCall in Beach Music. In this memoir, Conroy unflinchingly reveals that his father, fighter pilot Donald Conroy, was actually much worse than the abusive Meechum in his novel. Telling the truth also forces the author to confront a number of difficult realizations about himself. “I was born with a delusion in my soul that I’ve fought a rearguard battle with my entire life,” he writes. “Though I’m very much my mother’s boy, it has pained me to admit the blood of Santini rushes hard and fast in my bloodstream. My mother gave me a poet’s sensibility; my father’s DNA assured me that I was always ready for a fight, and that I could ride into any fray as a field-tested lord of battle.” Conroy lovingly describes his mother, whom he admits he idealized in The Great Santini and corrects for this book. Although his father’s fearsome persona never really changed, Conroy learned to forgive and even sympathize with his father, who would attend book signings with his son and good-naturedly satirize his own terrifying image. Less droll is the story of Conroy’s younger brother, Tom, who flung himself off a building in a suicidal fit of schizophrenia, and Conroy’s combative relationship with his sister, the poet Carol Conroy. The moving true story of an unforgiveable father and his unlikely redemption.”