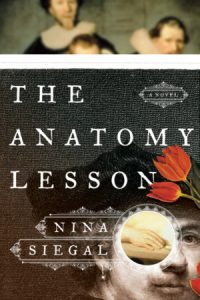

Reviews

Review Excerpts

New York Times – August 31, 2014

“The painting (The Anatomy Lesson) propelled Rembrandt to fame but did nothing for Kindt (the hanged thief) With a fictional assist, Siegal evens the score, breathing life into history and granting him a tenderhearted lover… the novelist revives the body that science and art preserved.”

New Yorker – June 7, 2014

“Siegal succeeds in the task she set for herself – to transmute her material into a work of art.”

HistoricalNovelSociety.org – May 1, 2014

Offering a glimpse into a distant place and era often requires a sleight-of-hand trick or two from writers. They produce the flavor of the place and times, sometimes with scanty details, relying on plot and characters to carry most of the story. That is not the case with The Anatomy Lesson. Virtually every sentence is drenched in the atmosphere of 17th-century Amsterdam. We feel as if we are walking at Rembrandt’s side, in a cell awaiting the execution of a thief, rushing through the streets with the condemned’s lover in hopes of saving him. This is a novel to be absorbed for its rich evocation of a single day when one man died and another rose to fame for his art.

True, Siegal’s masterful imagining of the tale behind the famous painting that launched Rembrandt’s career holds no surprises. We know that Aris the thief will end up on Dr. Nicolaes Tulp’s slab. And yet we are drawn to read on. Siegal chooses to tell the tale through seven well-focused points of view. The players are labeled with an aspect of either body or mind, necessary to keep them straight, since all seven narrate from the first-person perspective. And so, Aris the thief is (or will be) The Body. Flora, the woman bearing his child, is (appropriately) The Heart. Fetchet, the procurer of cadavers and oddities, is The Mouth. Descartes, the famous philosopher, stands in as The Mind. Nicolaes Tulp, as the anatomist, is The Hand. And Rembrandt himself, observing all that happens, is The Eyes. The seventh voice we hear is of Pia, a 21st-century art historian. Getting used to hearing so many characters speaking up as “I” takes awhile, but once one is acclimated there is little to do but sit back and soak up the 17th century for as long as this brilliant novel lasts.

Publishers Weekly – January 31, 2014

Siegal (A Little Trouble With the Facts) sets her splendid, gory second novel in 1623 in Amsterdam, where a thief’s execution occasions a celebration, evoking “bloodlust” throughout the city on “Justice Day.” Some of the narrators are famous men: Rembrandt, who painted Anatomical Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, on which the novel is based, and Descartes, who is “‘search[ing] for the soul in the body.'” Siegal gives voice not only to artists and philosophers, but also to the condemned man Adriaen Adriaenszoon, among others. Adriaen pleads, “‘[T]here is no evil in my breast.'” The evil, Siegal hints, might well lie in a place where Justice Day is received with such pleasure. Adriaen’s pregnant lover, Flora, is the only person clamoring for possession of the man’s body out of love—to give it a “Christian burial” after she fails to convince a clerk at the town hall to issue a pardon. Alive, Adriaen’s body is “beaten and branded” by his Calvinist father and by several Dutch towns. As a mere object, people want his corpse “for science” and “for art.” “All of us sought his flesh,” Rembrandt muses. Through masterful use of subtle details, embroidered into beautiful writing, Siegal suggests that art and violence often intertwine.