LA Times Profile

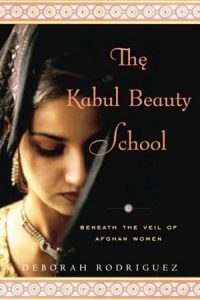

| Los Angeles Times – April 18, 2007 That’s the beauty of it Deborah Rodriguez wanted to help in Afghanistan. Turned out, women there needed her skills. She chronicles her work in the book ‘Kabul Beauty School.’ By Laura King KABUL, Afghanistan — Deborah Rodriguez has an explanation, of sorts, as to how a twice-divorced cosmetician from Michigan wound up running a beauty academy in the most incongruous of locales: the dusty, chaotic and blast-barricaded Afghan capital.”Something about this place — well, something about it just really brings out the hairdresser in me,” she said with a wave of her scarlet-lacquered fingernails. “The hairdresser in me” is a kind of personal shorthand for the character traits on ready display in Rodriguez’s engaging new memoir, “Kabul Beauty School: An American Woman Goes Behind the Veil” — curiosity, pluck, an abiding love of dishy gossip and a warm bond of sisterhood with the women of her adopted country. Together with a close-knit band of former beauty-academy students, Rodriguez presides over what is perhaps the world’s only high-end hair salon that is guarded by a gunman and heated by a sooty woodstove, with top-of-the-line beauty products stored in a chilly metal shipping container perched atop a mud-brick wall in the weedy yard. In the book, published this month by Random House and co-written with Kristin Ohlson, tales of blond highlights and Brazilian waxes blend with a portrait of a society struggling to find its footing five years after the fall of the Taliban — one in which fear and oppression still fall most heavily on women. In Kabul’s expatriate community and beyond, the 46-year-old Rodriguez is known as “Miss Debbie,” a flamboyant figure with a waist-length waterfall of hair in a shade of red she cheerfully describes as “one not found in nature.” She came to Afghanistan as a volunteer aid worker months after the Sept. 11 attacks and the subsequent fall of the Taliban, uncertain whether she had the skills to make any dent in the despair and disarray she saw around her. Rodriguez found her niche when she made two important discoveries: that for Afghan women, the beauty trade had been a treasured but perilous source of underground income during the Taliban era, and that Kabul was full of Western diplomats, journalists and aid workers who were simply desperate for a decent haircut. A much-needed skill As word of her skills spread — she had been working as a hairdresser since the age of 15 — Rodriguez would return to her guesthouse room to find the door plastered with notes from foreigners pleading for an appointment. “It was like they were searching for water in the desert!” she recalled. She obligingly made the after-hours rounds with scissors and permanent-wave solution in hand, improvising her way through cold water, curfews and power outages. At the same time, Rodriguez was meeting Afghan women and realizing how limited were their opportunities for earning a livelihood. Due in large measure to the traditional beliefs of their husbands and fathers, relatively few were able to work outside the home, even once the Taliban had been toppled. With the country having been closed off from the outside world for years, Afghan beauticians who had previously managed to eke out a living from “secret salons” in their homes were badly in need of training and supplies if they wanted to launch themselves in business. The heart of the book is Rodriguez’s relationship with the women she befriended in the beauty academy, which was originally established with other American hairdressers and became the subject of a documentary film. She helped some of her students found their own small salons but plucked out the most talented ones for lucrative jobs in her Oasis salon in the center of Kabul, which has a mainly foreign clientele and charges Western-style prices — money that is then plowed back into the beauty school. On any working day, the salon has the intimacy of a sorority or a harem, a steamy and sweet-smelling sanctuary in a city whose streets are patrolled by armored vehicles and that echoes several times a day with the sound of explosions or small-arms fire. The stories of the women, who are given pseudonyms in the book to protect them, are a troubling and fascinating snapshot of life in today’s Afghanistan. One’s father-in-law considers her a prostitute for working as a beautician. Another’s Taliban husband beats her and confiscates her earnings. Another was forced into marriage as a teenager with a much older man. In the book’s opening chapter, a description of the elaborate Afghan pre-wedding beauty ritual is interwoven with the gradual revelation of the bride’s terror that her new husband’s family will discover her secret — that she is not a virgin — and kill her. Rodriguez helps the girl devise a subterfuge to save herself. As the salon’s clients come and go, the beauticians drink tea, toy with one another’s hair and makeup, gossip freely and talk haltingly, sometimes with piercing simplicity, of their troubles. “Only God understands my sorrows,” one of Rodriguez’s protégés murmured as she carefully scrutinized a customer’s eyebrows in preparation for a “threading” to remove excess hairs. The day wore on, and peals of raucous laughter alternated with an occasional bout of tears. Everyone joined in both. Rodriguez can relate to the complex and difficult lives of her Afghan co-workers, she said, in part because her own life has taken a turn she never imagined. Three years ago, after an acquaintance of just 20 days, she married an Afghan man a decade her junior — who already had a wife and children living in exile in Saudi Arabia. Thus the book’s overarching theme of women’s empowerment is shot through with descriptions of Rodriguez’s struggles, including her scalding jealousy when her Afghan husband’s other wife gave birth to another child, two years after they married. Moreover, her husband is an aide and onetime comrade-in-arms of Abdul Rashid Dostum, an Afghan militia leader who is now a member of the government of President Hamid Karzai. International organizations, including Human Rights Watch, have called for Dostum to be put on trial for war crimes — a scenario unlikely under a general amnesty recently approved by the Afghan government. She’s a fighter — as is he Rodriguez’s sometimes-jocular references to her husband’s colorful career have had some unwelcome repercussions. Earlier this year, a British newspaper ran a profile of her under the witty but wounding headline: “Reader, she married a warlord.” “He’s not a warlord,” she said, her green eyes filling with tears. But she does refer to him a “mooj” — a mujahedin, a fighter. Her husband, who is called “Sam” in the book, was with Dostum when the Northern Alliance battled the Taliban and now advises him on foreign affairs. “He’s a warrior at heart,” she said. “But then, so am I.” The book is written in much the style in which Rodriguez speaks — full of vivid descriptions and funny asides. The love story between her and “Sam,” who spoke almost no English when they married, has some oddly charming moments. Once, in a romantic fervor, she called him to the balcony to look at what she thought were shooting stars. He gently informed her that they were missiles. As a novice author, Rodriguez was nervous about the book’s reception. But reviews have generally been favorable, with some predicting it is all but tailored for massive success with book clubs. The influential Kirkus Reviews called it “terrifically readable … rich in personal stories.” Rodriguez, the mother of two grown sons, said she finds it hard to envision a permanent return to the United States, though she is embarking on an extensive book tour and will be away from the salon and the beauty school for longer than she has been since her arrival in Afghanistan. Even when she pokes fun at herself as an incorrigible “loudmouth,” Rodriguez says she believes she is speaking up for Afghan women in a way that they have not been able — so far — to speak up for themselves. Change is coming, she believes, but progress is painfully slow. “Well, that’s when I can finally stop talking,” she said. “When their voices are heard.” |

|