The Story Behind the Book

The essay below was written after Bob’ s first encounter with Jeopardy! It appeared under the name THUMBS OF STEEL – My Year in Jeopardy! © Bob Harris, 1998

If you witnessed my $100,000 Jeopardy! Tournament Of Champions flame-out, you already know why I’m worried. If not, you will soon.

My genetic Lotto ticket didn’t reveal great strength, a square jaw, or even a full head of hair. The only good deal I’ve got going is an occasional ability to remember decent amounts of often useless information.

As I write this very sentence, I can recite the starting lineup of almost any Cleveland sports team, from any year since I was a kid. I also have no idea where my car keys are.

The previous two sentences are not a joke.

There’s rarely much immediate reward for this particular skill. At parties in college, I almost always lost the interest of attractive females to some larger predator, usually one whose job required his name to appear on his shirt.

My only consolation was being able to describe the process afterward in great detail.

However, I now live in Los Angeles, where television producers frequently hand out big chunks of cash in exchange for brain clutter. So after a few weeks of working up the nerve, I decided to take the Jeopardy! contestant test.

I failed.

They give the test in the actual Jeopardy! studio to almost any warm body who calls and signs up. Usually, these warm bodies tend to be white, male, and upper-middle class. This is not the show’s fault; in fact, the producers would strongly prefer a diverse group. But Jeopardy! requires education, and in the U.S., education requires money. So inevitably, the crowd of auditioners often looks like a Forbes For President rally.

The test consists of fifty of the show’s most difficult $800- and $1000-level questions, mostly concerning history, the liberal arts, geography, and other almanac stuff. The sciences, however, are all but invisible. This should be no big surprise. Most of the writers, after all, are writers.

I’m at a disadvantage, since I don’t read a lot of fiction (reality is plenty imaginative, thanks) and my major was electrical engineering. So while I’ve got the 1979 Cleveland Indians fully armed and ready to attack, I know exactly squat about a lot of Jeopardy! categories. Italian Opera, French Literature, or Eastern Religion might as well be Precambrian Mime, Antarctic Mythology, and Neptunian Folksong.

Still, if the Jeopardy! buzzers stop working, just get me a soldering iron and stand back.

So I tried. And failed.

No shame in that. Over 100 people show up for a typical test. Maybe a dozen get to stick around.

I went home.

However, they do let you come back every six months if you’re silly enough to keep trying.

So I failed again. And again. And again.

There are probably stalkers who give up more easily.

On the fifth trip (I think; I actually lost count), in February 1997, I resigned myself to endless washouts. As I locked my car in the Sony parking garage, I resolved never to bother these nice people again.

Naturally, that was the day I passed.

After the test, you play a mock game against two other candidates. The key here isn’t brains, but small motor skills. A surprising number of otherwise normal people have remarkable difficulty simply pushing a button and speaking clearly. If that seems hard to believe, eat your next meal at a drive-thru. Take notes if necessary.

After just a few questions of pretend-Jeopardy!, subtle petty gamesmanship already begins. Auditioners begin peeking ahead at the questions, name-dropping alma maters, and kissing up to the producers. None of this works. The producers have seen it all before, and while they’re actually extremely friendly people, being complimented on their hair is not an important part of their jobs.

Next comes a brief interview, roughly as complex as the questions asked at the Miss America pageant. You’ve already demonstrated intellectual and physical prowess. Now they’re looking for interpersonal skill. A good Jeopardy! player is free of major tics, quirks, and unseemly obsessions. Hissing at other contestants, handing out literature from an Unorganized Militia, and channeling dead relatives are all good ways to stay off the show.

Finally, once you’ve been certified as Alex-safe, they ask you to fill out a form, listing five funny and notable things about your life that can be summarized in two sentences. If you’re lucky enough to get on the show, these will be the topics on the card in Alex’s hand when he greets you.

They give you five minutes.

This actually is the hardest part. Try it yourself. Most interesting things aren’t short, and vice versa.

I ran out of ideas after four. I ran out of time a moment later.

On the last line, I scribbled down that I like squirrels.

After the interview, you go home and resume your life. They might call in six months. They might not call, ever.

Some people think Jeopardy! gives contestants an outline of what subjects to study or what sort of questions they might expect. Nope. In fact, since they can ask about anything that ever happened anywhere at any time to anybody, the producers quite bluntly insist that only a fool would actually try to study for the show.

I got a call from the producers in late August.

They had scheduled me for a taping date in mid-September.

I now had just weeks to suck in a complete liberal arts education.

Day after day, I disappeared into the Reference section like Shoeless Joe into a cornfield, compiling context-free lists — titles and authors, capitals and presidents, battles and generals — into a large spiral-bound notebook.

At 7 p.m., I would stop everything to watch the show, trying to study betting strategies, get a handle on frequent categories, and evaluate my preparedness.

At 7:30, I went back to the notebook, reviewing my recent discoveries.

At no point did I ever work this hard getting my degree.

In retrospect, my need for revenge against all the single-browed name-wearing girl-stealing predators kicked in bigtime. Suddenly nothing else mattered.

I blew off my own, actual, real-time girlfriend. Plates stacked up in the sink. Emails and phone calls backed up. I suspect that even my hygiene suffered.

In the second week, I started standing while playing along, the better to acclimate to actual game conditions. In my mind, since the Cleveland Browns played better in Denver after practicing in thin air, then it only made sense to practice Jeopardy! games while standing .

Silly as it sounds, this turns out to have been an excellent strategy. Psychologists actually have a term for improved performance due to similar physical stimulus: “state-dependent retrieval.”

My girlfriend called it “kinda nuts.”

Soon, I also realized that the video screens are far across the stage, so I moved my TV to the farthest corner of the apartment. A few days later, I realized that stage lights would be in my eyes, so I rearranged my halogen lamps to cast a blinding glare on me from all directions.

About here is the point where some of my friends started to worry.

Soon, I began taking mineral and herbal supplements to improve my mental acuity, and I devised a mathematical model by which a player at home might accurately estimate how he would have done against two other players in the studio.

I also developed what I believed to be (and I write these words as if confessing an indiscretion) an ergonomically-improved buzzer technique.

The buzzers are disabled while Alex reads each question; players must wait for an unseen stagehand to flip the “on” switch when Alex is finished, a moment indicated by a series of flashing pinlights surrounding the game board. Jump the lights, and your buzzer is briefly disabled again. Since many answers are known to all three players, at least a third of the money in every single game will always go to the player with the best buzzer skills.

Given that tens of thousands of dollars are flying around, players usually give their buzzer grip amazingly little thought. Most simply grab the thing like a banana and begin thumb-banging away. However, your index finger is not only more sensitive, it’s used for a vastly greater assortment of daily fine motor tasks.

After much experimentation, I abandoned the standard thumb-on-button technique, in favor of a fatigue-reducing desk-supported index-finger maneuver I considered the Jeopardy! equivalent of the Fosbury Flop.

Perhaps counseling would not have been out of the question.

And suddenly there I was, out walked Alex, and off we went.

My kung fu buzzer grip seemed to pay instant dividends. The studying paid off, too: in the very first minute I was on the show, there I was, saying “who is Henry James?” with confidence, as if the novelist’s works lined my shelves.

In reality, not only had I never read any of Henry James’ books, I had only the barest idea who he was.

I had completely forgotten ever saying that I liked squirrels.

This was how Alex Trebek introduced me to America: “Bob Harris has a fascination — some might say an obsession — with which animal?”

For a moment, I wondered how it would look if I couldn’t even answer a question about my own life.

Then I remembered the hurried scribble from months earlier, and Alex began teasing me about admiring an animal that steals food. I teased him right back, saying something like “maybe if you lived in a tree, you’d do the same thing.”

The audience laughed. Alex looked taken slightly aback, then smiled. Apparently most contestants are too shy to tease him back. He took it well. I was grateful. The last thing I needed was to accidentally get into a slap-fight on national TV.

The rest of that first visit to the show is a complete blur. Jeopardy! tapes five games in a single day. By the time it’s over, even if you’ve done well, there’s little left in your brain but exhaustion and a large smudge of memory narrated by Johnny Gilbert.

I do know that at one point in my fourth show, I somehow ran through the entire category of London City Guilds, about which I promise I know nothing. But there I am on the videotape, asking “what are the Fishmongers?” with no hesitation whatsoever.

I still have no idea how that happened. Fishmongers aren’t even in my notebook. I checked.

While writing the last few paragraphs, I gradually came to believe that my car keys are on the kitchen counter.

They are not.

The games flew by. The other contestants hadn’t prepared nearly as well.

They had lives.

I kicked ass.

If you win five games, Jeopardy! also gives you about $40,000 worth of automobile as a bonus, plus a spot in the Tournament of Champions. Then they quietly hustle you off before Merv Griffin has to sell off one of his islands.

Thus, my last Final Jeopardy answer — one single question — was worth more money than the house I grew up in.

During the commercial, the make-up girl told me I looked pale.

On the tape, I have the same skin tone as Nixon during his resignation speech.

After the shows aired, I was frequently recognized for weeks. Twenty million people really do watch. I couldn’t eat a fast-food burrito without somebody asking me to repeat the $1000 term for glowing bacteria on rotting meat (“what is bioluminescence?”).

This didn’t exactly make the burrito any more appetizing.

Women I barely knew began asking me out. My email inbox collected marriage proposals from distant college professors and mash notes from girls who had broken up with me two decades earlier. Relatives I didn’t know suddenly materialized.

Even my own girlfriend started speaking to me again.

Almost everyone asked (and will continue to ask until the day I die) what Alex Trebek is really like, as if I might actually have a clue.

Perhaps people imagine that after the shows we all stroll off to the lush Jeopardy! mansion, with Alex playing the role of Hef, garbed in a silk kimono inscribed with a giant script “J!” on the left breast. As evening gently falls, Al Jarreau sings in the garden while fifteen contestants all sink into a hot tub, sipping Potent Potables with Vanna, Charo and Zsa Zsa.

I suppose that’s possible. But I can’t confirm it, anyway.

Or maybe people are seeking tabloid titillation, hoping to learn that Alex Trebek is actually a five-foot-tall Cuban cross-dresser from Mississippi, pregnant with Pat Sajak’s love child. Jeopardy!, we discover, does wonders with make-up.

I cannot confirm this, either.

Unfortunately, I know only slightly more about Alex Trebek than I do about Henry James. This is what I would write in my spiral notebook if necessary, in full: he’s extremely smart, very good at playing traffic cop among bright people wrestling with nerves, and eager to engage in a playful give-and-take whenever he feels comfortable.

I teased him. He teased me back. Also, when we first met, he asked me exactly 302 questions, not counting the one about squirrels. I don’t believe I’ve ever asked him anything.

So the relationship is just a little one-sided.

My banter with Alex also had a side benefit, one I hadn’t intended but happily exploited once it appeared: in any band of primates, proximity to the Alpha Male confers status.

Every contestant is nervous during their first game. A few are even a little star-struck when the Alex Trebek suddenly saunters out and the game begins.

If being the returning champ provided me a small psychological edge, appearing comfortable enough to tease Alex, even slightly, increased that advantage palpably. One contestant even let out a small, involuntary, helpless-sounding sigh when Alex grinned at a small remark I made.

Game over, I thought, and it had barely begun.

The players against whom I was matched were invariably funny and kind, and the long stressful morning in the green room before taping was stressful enough that many of us bonded like survivors of an airline disaster. A few have since become my good friends.

Still, some of these people knew who Henry James actually was. So I joked around as much as I could. After all, I was there to win.

Perhaps the funniest shot Alex ever launched back at me came a few months later, while he was taping a series of promos for the upcoming Tournament of Champions. In one version, he described the contestants as “some of the best minds we’ve ever had… [then, whispering:] except Bob.”

I didn’t realize those words would be prophetic.

The Tournament was scheduled for January 1998, to air in February. I therefore enjoyed a brief visit with reality for a few weeks in October before returning to a routine of practice games played in blinding light with a distant TV.

Halloween came. I had forgotten to buy candy, so I handed out Gingko Biloba supplements.

Thanksgiving came. Instead of visiting my family in Ohio, I spent the weekend studying Famous American Indians.

On Christmas morning, I memorized Catholic Saints, and on New Year’s Eve, I learned the names of 20th Century Dancers.

An intervention by the Cult Awareness Network might have been in order.

The Tournament contestants were the smartest people I’ve ever met: a doctor who completed med school at 23, a teenage whiz-kid who scored 1600 on his SATs, and (most intimidating of all) Dan Melia, a professor of Celtic Studies at Berkeley who had actually read all of the books whose titles I had merely memorized.

Joking around with Alex wasn’t going to do a damn thing to these people. In fact, if a nuclear holocaust had destroyed the world but somehow spared the Jeopardy! green room, these people could have rebuilt Western Civilization all by themselves.

I would have been the one wearing my name on my shirt. For the first time in my life, I was the cute, stupid guy.

Sure enough, I lived up to the role: in exhausting myself with months of study, the one category I had neglected was Human Limitations.

The night before the Tournament began, I came down with a rampaging flu. Five minutes before my first match began, I could barely make myself stand. As Johnny Gilbert began our introductions, my brain was so muddied that I couldn’t quite make out my own name

.

Still, there was an upside: I realized at that moment that I would no longer fear death, for I was about to enter Hell.

Against the smartest, quickest minds on Earth, I couldn’t even remember that Snoopy was a beagle.

A few of the other contestants quietly snickered at my performance. I silently resolved to exhale on them at the first opportunity.

My score was tiny entering Final Jeopardy, which asked us to name an old U.S. city named for the Bishop of Hippo, a title which I had never heard of. Clearing bizarre cartoon images from my mind, I scrawled down the name of the oldest U.S. city I could think of that had a Catholic-sounding name, and then I prepared to go home.

A minute later, I found out that St. Augustine was, in fact, the Bishop of Hippo.

My fever was peaking at 102. I had to get some rest, because I would be playing again the next day.

But first I had to go breathe on a few people.

The next morning, my fever was down. I played the game of my life, racked up my highest score, and entered the two-day $100,000 final as the #1 seed.

The Berkeley professor, Dan Melia, was the #2 seed.

Uh-oh.

The #3 seed was Kim Worth, a fellow stand-up comedian I had actually met once before, working a bar gig in a small town in Wisconsin that neither one of us remembers.

Aside to the people of Wisconsin: you have a town up there so forgettable that two Jeopardy! champions can’t remember a thing about it.

Perhaps you should think about starting a pumpkin festival.

As the two-game final started in the afternoon, my knowledge of buzzer kendo kept me afloat through most of the easy questions, and I was ahead after the first round. Soon, however, Dan began nailing $1000 questions I could barely conceptualize.

This was mortifying.

How could this be? Could Dan’s wealth of hard-earned education, knowledge, and experience finally overcome my unstable amalgam of Cliff’s Notes, flash-cards, and three-card monte?

I was determined not to let that happen.

As Double Jeopardy of the first game concluded, my best chance to win would be to pick a spot and try to nail a huge bet. But when? Where? I needed an edge. Think, man, think…

It’s not unusual for Jeopardy! to tailor questions to the show’s scheduled broadcast date. My very first game had been scheduled for Halloween, so one entire category on that September day was devoted to Famous Monsters.

The broadcast date of this particular game was… um… February 12th. OK, that’s… hmm… Lincoln’s birthday.

Just as I realized this, Alex walked over to the game board and revealed the Final Jeopardy category…

U.S. Presidents.

YES! We were probably about to get some obscure Lincoln question about the Union Party, Mary Surratt, or the Black Hawk War.

If my hunch was right, I could close the whole deal before the second game even started. If not, I’d probably still wind up exactly where I was headed anyway.

So I bet every dollar I had.

The question had nothing to do with Lincoln.

The correct answer to what they did ask was John Quincy Adams. It wasn’t even a particularly difficult question.

Being the cute, stupid guy was a lot less thrilling than I had expected.

Worse, I was compelled to spend another 30 minutes on national TV with no chance to win. So I played the whole thing for laughs, as did Kim. The audience roared. People like a good loser.

I can’t speak for Kim, but I wasn’t being gracious. I just don’t know how else to look dignified while getting pasted.

When it was over, the three of us shared a nice ovation from the crowd. Later on, we all went out to a nice dinner and drank a bottle of champagne.

Dan picked up the check.

At least the whole shebang made an impression. As this story goes to press (June 1998), two major airlines have begun showing the Tournament finals as in-flight entertainment. A dozen colleges (none of which I remember at the moment) have invited me to speak on memory skills. And the Associated Press has even carried a national story concerning my index-finger buzzer technique (dubbed the “Harris Hit” by the AP writer) which is now frequently used by other contestants, although absolutely no one ever uses that name.

I may always be haunted by visions of John Quincy Adams jumping at me from Lincoln’s shadow. If screwing up on television can kill you, I may already be a dead man.

Still, when I first began performing, I dreamed of making millions of people laugh, if just once in my life.

It didn’t happen the way I’d imagined. But it did happen.

It wasn’t the prize I was playing for. But I’ll take it.

Postscript:

While finishing this article, I finally located my car keys. They’re in my blue jeans, downstairs, making a horrible racket in the dryer.

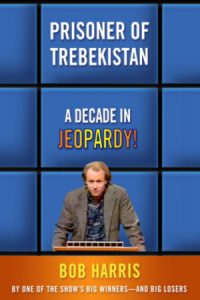

About the author

BOB HARRIS has written for National Lampoon, Mother Jones online, and CSI: Crime Scene Investigation. In addition to being an undefeated 5-time Jeopardy! champion, he reached the finals of the annual Tournament of Champions before losing so absurdly that the episodes were shown on airlines as in-flight entertainment. In 2002, Bob was one of only 15 players invited to compete in a Million-Dollar Masters Tournament held at Radio City Music Hall. More recently, he was a memorable part of the 2005 Ultimate Tournament of Champions. He lives in Los Angeles.