The Story Behind the Book

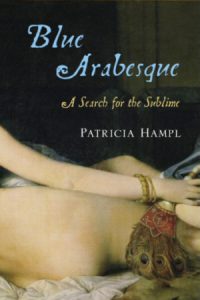

BLUE ARABESQUE: A Search For The Sublime by Patricia Hampl

This Matisse woman looked modern and she looked thoughtful. Just what I wanted to be: a thoughtful modern woman. Independent, free, thinking my own thoughts. That’s how she struck me. I had just learned to call myself a “feminist,” though in 1972 the word, newly adopted by my gallant generation, sounded faintly antique, as if we were intent on becoming latter day suffragists. I was just starting to write poetry, so I wrote a poem about the woman in the painting who had so captivated me, this aloof, rather asexual figure safe in her contemplative gaze. Though I didn’t see it at the time, she was something of a nun—and of course I had been educated by nuns. The poem was, I see now, an unconscious manifesto, a covert wish for the cloister. A curious line is hiding (I think of it now as “hiding”) in the center of the poem:

The only power of the woman:

To be untouchable….

It was the title poem of my first book, Woman Before an Aquarium published in 1978. [I have copied the poem at the end of this statement.]

It was perhaps a sad choice for a young woman—to choose the “untouchable” woman as a model. But my life as a writer began with this bookish girl, a sort of secularized nun. But over the years this attachment deepened into a fascination with Matisse and his fascination with an opposite female image—the odalisque, the models he hired to be faux harem girls. He painted these figures obsessively during the years between the two World Wars on the Cote d’Azur while the world held its breath between devastations. In these paintings that his contemporaries thought were decorative indulgences, he pondered the great questions of light and color that also obsessed him, preoccupations that were, for him, nothing less than the core mysteries of the created world.

With these women, set in lavishly figured backgrounds, Matisse painted his way into the heart of leisure, of privacy, of languor, values absolutely at odds with the modern world’s notions of progress and material power. He made of his studio a “pocket paradise.” He was painting the blue world behind that Moroccan screen I first saw in the Chicago Art Institute. I came to see his singular focus, his refusal to give up his obsession and his insistence on lusciousness as a form of integrity. He wanted, he said, to paint “all of his feeling.” I recognized in him and in this determination exactly how I saw the purpose of art and of poetry and all imaginative writing in modern times—to render “all one’s feeling.” The personal wasn’t simply political—as we said in the 70s. It was spiritual. Even these odalisques were cloistered, contemplative bodies Matisse arrayed like saints in his cell above the Mediterranean.

As a northerner—Matisse came from Picardy, the Minnesota/Dakota of France—I also shared his permanently astonished delight in the light and air of the Riviera. Having started out as a young poet with a poem in which I apparently longed to be a nun—even if an arty secular nun–I wanted now, years later, to write a book about the “other” Matisse woman, the odalisque, the very figure my earnest “feminist” self could not take in. I’m not sure, in the end, that I strayed very far from my original fascination with the contemplative woman. This book has taken me into the heart of Matisse’s cloister, which is to say “all his feeling” and—I hope—into my own.

WOMAN BEFORE AN AQUARIUM

by Patricia HamplThe goldfish ticks silently,

Little finned gold watch

on its chain of water,

swaying over the rivulets of the brain,

over the hard rocks and spiney shells.The world is round, distorted

the clerk said when I insisted

on a round fishbowl.

Now, like a Matisse woman,

I study my lesson slowly,

crushing a warm pinecone

in my hand, releasing

the resin, its memory of wild nights,

my Indian back crushing

the pine needles, the trapper

standing over me, his white-dead skin.Fear of the crushing,

fear of the human smell.

A Matisse woman always wants

to be a mermaid,

her odalisque body

stretches pale and heavy

before her and the exotic wall hangings;

the only power of the woman:

to be untouchable.But dressed, a simple Western face,

a schoolgirl’s haircut, the plain desk

of ordinary work, she sits

crushing the pinecone of fear,

not knowing it is fear.

The paper before her is blank.The aquarium sits like a lantern,

a green inner light, round

and green, a souvenir

from the underworld,

its gold residents opening and closing

their wordless mouths.I am on the shore of the room,

glinting inside

with the flick of water,

heart ticking with the message

of biology to a kindred species.

The mermaid—not the enchantress,

but the mermaid of double life—

sits on the rock, combing

the golden strands of human hair,

thinking as always

of swimming.