The Story Behind the Book

Caroline Stoessinger on the inspirations behind her life and book,

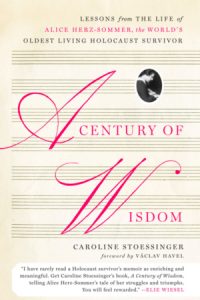

A CENTURY OF WISDOM: Lessons from the Life of Alice Herz-Sommer, the World’s Oldest Living Holocaust Survivor

As a young child growing up in the small town of Thayer, Missouri (population 900) in the Ozark Mountains, I had no idea how or where to find the world, but I was certain it was somewhere else. Music became my escape route… and all roads ultimately led to Alice.

When I was four, my parents bought me a small piano, a Kimball spinet, with a $15 down payment and $5 monthly fees over the next four years. Mother said I would learn music by important people –Beethoven, Mozart and Bach. Life was looking up.

When I was nine, Carter’s Funeral Home acquired a Hammond Organ (the first in Our Town) and hired me to play for $1 per funeral. I discovered that I could improvise on sad sounding tunes while the mourners waited in line for their final peek into the open casket. My career was improving.

Later that year, I was invited to play a fifteen-minute piano recital at the new radio station in West Plains, a large town with a population of 3,000 twenty-five miles north of my home. Entrance into the world of radio ignited my imagination. It was a way to travel, musically. Since the local teachers, preachers and other community leaders knew nothing of classical music, I thought this would be the best way to spread the word. By the time I was ten, I was running a weekly classical music radio show.

It was around this time that I began traveling unaccompanied to Memphis (4 hours by train) every Saturday to take piano and organ lessons at Southwestern University (renamed Rhodes College today). In Memphis, I heard acclaimed pianist Arthur Rubenstein in recital. Afterwards, I made someone take me to his hotel where I met him in the lobby. He was very kind and advised me to read great books and practice.

My most important break came when I accompanied George Hearn who introduced me to Cliff Pierce. Both had summer jobs in a Y camp near our swimming hole. George (later a Broadway star) and Cliff were surprised to find a pianist in those hills and visited me every Wednesday night to sing and eat my mother’s fried chicken. Cliff, a Yale student, told me that I must go to an Ivy League school in the East, and I heard the names Harvard and Columbia for the first time. My world was expanding.

I attended Barnard College in New York and studied privately with a Juilliard teacher in the halls of Columbia University when I unwittingly began my producing career. I organized a benefit concert for Hungarian Refugees at Columbia’s McMillan Theater performed by the Budapest String Quartet with Helen Hayes as the Honorary Chair. As word of my activities spread, Barnard’s president called me into her office and said, “My dear, what you are doing is lovely, but the hall must be filled. The college must not be embarrassed. “ Miraculously all of the tickets were sold. I went on to graduate school at the Eastman School of Music at the University of Rochester, where I earned a Master of Music degree.

During my Barnard years, the one person who gave me life altering advice wasn’t a professor, but the future president of the United States. I was selected by the Office of Student Affairs to interview Senator Kennedy (on behalf of the college) for NBC’s morning television program. Afterwards, I sat with the Senator and Jackie over breakfast in the NBC studio where Kennedy asked me a lot of questions and then said, “Politics is a dirty business. Stick to your music so you can bring beauty into the world.” I have always regretted that he died before I could properly thank him for his seminal advice.

My first job was working for Friedberg Artist’s Management as a personal assistant to the great pianist, Dame Myra Hess. One night in her dressing room, she took a scrap of yellowed paper out of a worn leather purse and said, “This is my story, look.” The numbers 576 were inscribed on her keepsake. She explained, “This is the number of concerts I played during the war in the National Gallery in London. It was my contribution to the war effort and I believe it helped.” She went on to tell me of a sailor who she ran into years after the war when he was a civilian walking around Trafalgar Square. He told her that he and his fellow officers never missed a concert while on a day’s leave. “Nobody told them that Beethoven and Mozart were too high-brow or beyond their understanding; they just sat back, listened, and a new world opened to them,” Dame Myra proceeded to tell me. Her experience at the National Gallery proved beyond a doubt how real the need for music was in the lives of people in almost every walk of life. Finally, I had found my mentor.

Music brought me together with my future husband. He introduced himself to me at a UN reception because I had a Bach score in my hands. He was an Austrian-Czech refugee who had lost his grandparents and most of his family in the Holocaust. After his grandparents were arrested and imprisoned in Theresienstadt concentration camp, he and his parents escaped from Prague. In college, I had heard rumors about Theresienstadt, a camp where musicians performed concerts before they were deported to their deaths in Auschwitz. But information about the camp outside Prague was minimal.

Through my husband and his mother, I began to meet numerous refugees and survivors and began a life-long journey to piece together the heart-breaking story of musicians in Theresienstadt and music of the Holocaust. When we traveled to Prague in the 1970s, my questions were met with silence or rebuff. Only after 1990 (when Vaclav Havel became the first free President) did I visit Theresienstadt and finally obtain access to scores of music composed in the camp that was held in the National Archives and to interview survivors of the camps.

Guided by Dame Myra’s inspiration, which resonated with my own beliefs, I began to produce concerts with the purposes of educating the public to the humanizing value of music in the life of the individual and in the community. I produced more than 100 Concerts for Peace each year, often the premiere of a work composed in Theresienstadt, that were free to the public—warming the hearts and opening the minds of the large audiences. And I created the annual New Year’s Eve Concert for Peace at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, which more than 10,000 people—from aristocrats to the homeless—crowded into the cathedral to enjoy a baroque concert with Frederica Von Stade, William Warfield and Leonard Bernstein. It was as democratic as it was uplifting, and a spiritual way to start a new beginning each year.

My daughter began to say about me, “Everything you do or say leads back to World War II.” She was correct. I continued to interview survivors and children of survivors. In Prague, I spent time with Karel Berman who had known Alice Herz-Sommer both before the war and in Theresienstadt. He talked about the effects the performances had on both the prisoners and artists, and I met men and women who had sung in Brundibar, the children’s opera Alice’s son and others performed in at the concentration camp.

I finally met Alice in London in 2004. She spoke of music as “our food”. Alice believes that music is basic to our education, to peace, and to our well-being. Inspired by her devotion to and profound belief in music, I founded the Mozart Academy, naming Alice honorary president.

As someone who survived the greatest degradation of the human spirit the world has ever known, Alice has been known as the best of mankind. She says, “Times have always been bad and today is no different. We need music in our lives more than ever. Music helped us to survive in the camps and music can help us today. We are a global society and music is the only language that needs no translation. Music brings us to peace. The power of music is universal.”

At 108, Alice practices several hours daily for the solace and enrichment of others. She is our model and our inspiration. We teach our students to enjoy their practice sessions and to love playing and attending concerts. We must make music lessons and concerts in our schools and in our communities available to the public at large (free or at minimal cost). The unimaginable life-long benefits far outweigh the costs. Music saves Alice’s life and it saves mine. Alice does not give up and neither will I.

It has been a privilege to be in her presence, to learn from her and to write her story.