The Story Behind the Book

One summer afternoon I was driving by a pizza place, a tiny take-out joint, the sight of which reminded me of the Italian social clubs that were once common throughout Chicago, and I imagined a young man with a dark vest and starched white shirt striding out of this club gripping a bottle of some sort, the owner’s son perhaps, and I knew I wanted to spend time in this place from the past. Though that scene never appeared in the novel, the quietude of that image stayed with me and drove me during the writing of this book.

I kept wondering, Why the stride, why the confidence? Who or what was waiting for this young man at home? I wasn’t sure, but a few certainties began to emerge: this was a Sunday stride, the day when a pot of red sauce and a bowl of fresh pasta brought the family together for a few hours, and to arrive home early meant he could pull a slice of warm bread from the newly baked loaf and dip it into the sauce and luxuriate in the aroma of meatballs frying in a pan until his old world mother ordered him out of the kitchen. Outside, in the backyard, there were plum tomatoes and bell peppers, of course, and an extended family of loud neighbors who seemed busy at doing nothing. But beyond that the greater neighborhood pulsed with its own stark needs and promises and threatened to disrupt the sanctity of these Sunday dinners.

Inhabiting such settings with particular people—and after a while they seem like people to me rather than just characters—is infinitely more challenging. While I can genuinely claim that the characters in this book are imaginary, I can’t deny the many parallels with my own life. My father immigrated to America when he was thirty-seven, a fact that never fails to astonish me. Six months later, after establishing himself, which meant he leased an apartment and found a job as a tailor in a factory in downtown Chicago, he sent for the rest of his family, a wife, a five-year-old son, and me, their eleven-month-old, who often wonders what my life would have been like had I stayed in Italy. I wonder about the physical, of course, running down dusty village roads; picking cherries in front of our stone farmhouse; taking in the mist-shrouded Apennines each morning; visiting my grandfather, a man I met only twice, though he lived an entire century. But mainly I wonder about language, how English has shaped my very thoughts, while my father could never hope to make this tongue his own.

While I feel fortunate, even redeemed, to have grown up hearing two tongues, I also feel loss. My siblings and I knew a crude Napolitano well enough to ask for another helping of cake or to explain we were going three houses down to play, but we could never fully express how we felt about anything. And because of their limitations, coming to English so late in their lives, my parents couldn’t share their stories with us. Our conversations then were limited to simple household matters. As a result, I craved stories and turned to comic books, began collecting them. Every Thursday I cashed in the pop bottles I’d scrounged from around the neighborhood for the newest World’s Finest and Superman and Batman. Eventually I discovered other kinds of writing, and between schoolyard softball games and pitching pennies along sidewalk squares, spent hours on my front stoop lost in the tales of Arthur Conan Doyle and Poe and many others I can’t even recall.

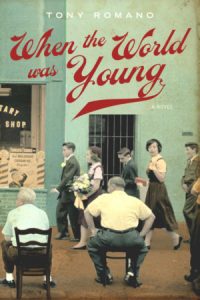

When I began writing my own short stories, which seemed to nourish me as much as my mother’s bread, they were largely autobiographical. After finishing When the World Was Young I thought I had finally broken free from my past and created a wholly imagined world, and in some respects I had. But mostly, I’m still the boy reading on the stoop, wondering, coming to grips with the familiar cycle of loss and redemption, this time through the Peccatori family breathing and working in Chicago in 1957, old friends to me now. How is it possible, I often wonder, to feel nostalgia for characters and places that don’t exist and for a time in which I never lived?

About the author

Tony Romano has been a high school teacher for 25 years. His fiction has appeared in the Chicago Tribune, Sou’wester, Whetstone, VIA: Voices in Italian Americana and has been nominated for two Pushcart Prizes. He is a two-time winner of a PEN Syndicated Fiction Project and his stories have been produced for National Public Radio’s The Sound of Writing series. He lives near Chicago, IL.