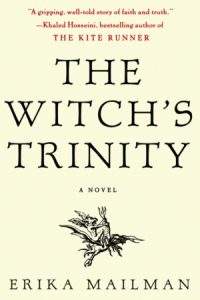

The Story Behind the Book

The trigger for this novel was listening to Teofilo F. Ruiz’s “The Terror of History” audiotapes in my car. A friend had loaned them to me, I was driving, and I had endured the long discussions of Catharists and mystics, just waiting for tape eight: The Witch Craze. When it came, it hit hard. Ruiz said women sometimes accused family members of witchcraft because they were so hungry. I thought, “What kind of hell does your life have to be, that you will offer up a family member so that there is one less plate upon the table?” I was appalled and shaken at this very different interpretation of the word “family.” (But then again, medieval people felt very differently about all kinds of relationships; infanticide was commonplace.)

I kept mulling this horrifying idea over. And then I hit on a plot element that I thought could help me write a novel: what if a woman were accused of witchcraft, but suffered from senile dementia and therefore didn’t know whether she was a witch?

I hunkered down with many books, including Jeffrey Burton Russell’s Witchcraft in the Middle Ages, to do as much research as I could. I was more writer than historian, I fear. However, much of what is included is truthful, but I have taken some liberties – for example, I found reference to a pebble test like Künne undergoes, but altered it from one pebble to three, to draw the comparison to the holy trinity.

Another valuable source was Amnesty International’s touring Torture exhibit, which I saw in San Francisco several years ago. I approached with a morbid, salacious curiosity, but was humbled by the true, real, sordid pain that humans inflict on each other. The worst feeling was to come, when I would bend down to read a placard and learn that the medieval device I’d just been looking at was still in use today.

A visceral source was joining the Schulplattler group, a German folk dance group connected to the Naturfreunde (Nature Friends) club in Oakland, California. Many of our dances date to medieval times, such as the Maypole Dance and the Miller’s Dance. Learning how to move my body in these ancient rhythms and patterns, aided by flying sweat and exuberance, felt like putting the needle down into the groove of an LP. It was a way to learn, to feel in the gut the simple earthy pleasures of Güde’s life.

Finally, my decision to set this novel in Germany just felt instinctual. I am of German heritage and, growing up in Vermont, I knew how much atmosphere mere snow can convey simply by being there. I wanted to create a world that was insular, bitingly cold and remote, wanted to offer the frightening thought that snow can effectively hide things.

When I pictured Güde’s village, I saw the bleak slumped huts of Brueghel’s The Hunters in the Snow (yes, it portrays Holland but near enough to Germany to be meaningful).

THE WITCH’S TRINITY is foremost a novel and it was not intended to be a resource for anyone researching European witchcraft, but it may offer a useful amalgam of information for those who are unaware that women perished in a 400-year cycle of suspicion and hatred. My hope is that it might inspire readers to do their own searching.