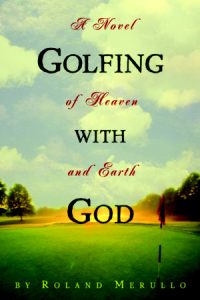

The Story Behind the Book

Golf. From the outside it looks like such a stupid activity, a bunch of overweight men riding around in a little cart, smoking cigars and fondling $300-dollar putters. They stop the cart, get out, make a series of ridiculous warm-up moves, hack up a tuft of grass, send a white ball squirting off into the river or the woods, curse, pose, spit. From the outside it looks like all they are doing is indulging some preposterous fantasy of themselves as athletes. . .athletes wearing two-tone shoes, and shirts that show their bellies.

But from the inside it’s not like that, at all. From the inside, the golf course is a manicured theme park in which you play out the triumphs and miseries of real life, only for lower stakes. You have a variety of tools at your disposal, tools you’ve spent hundreds of hours learning to use. You have the company of like-minded men and women, all of you engaged in a mostly silent dance governed by ancient rules. You can travel almost anywhere in the world –Zimbabwe, Italy, New Zealand, Thailand, Alaska, Korea, Japan, Sweden, China–and find golf courses; and you can be paired up with people who love the game as you do, who suffer from it as you do. Even without a common language, you can fall into a strange intimacy with these people because, playing golf, you cannot help but occasionally humiliate yourself–taking a hard swing and knocking the explosive little ball all of sixty feet. You curse, have a tantrum, make a joke, make an excuse, and you go on.

I first played golf with my father and uncles, working-class guys who hacked through nine holes on a weekend, smoking cigars and saying bad words. They were patient with me, generous in allowing me to play along when I didn’t know the elaborate dance of course etiquette. We played together once a week for a few years, and then, at the age of twenty, I gave up the game. I ran, rowed crew, played hockey, joined a karate school, and looked at golf again from the outside and saw how stupid it was.

At age 25, I broke my back in a bad fall and started in on a long career of dealing with pain. I married, and after eighteen childless years, my wife and I had a daughter, then another, and these two creatures became the joys of our middle age. We built an addition onto our house in the hills of western Massachusetts, and I was working on the roof of that addition with an old-timer when he mentioned a golf course that had been carved out of a dairy farm in the next town north. I found this course, gobbled some pain medication, started to play again, and fell in love with golf in a way that made the brief infatuation of my teenage years seem like one quick kiss on the cheek.

I became a devotee. I worshipped golf. Studied it. Practiced, read books, took lessons, made friends who were similarly obsessed. It soon became clear to me that golf, with its heartbreak and exultation, was a kind of metaphor for the spiritual adventure, something that had been an obsession of mine since I was very small. What are we doing here? Why do we suffer and die? Why do some people seem to suffer so much more than others? Why is there evil? Why is there beauty? Even as a ten-year-old I’d walked along the gray sand at Revere Beach, wondering obsessively about such things, and about the Roman Catholic idea of God that had been handed down to me.

In my twenties and thirties, I’d become a less devout Catholic and a more devout person. I had a daily meditation practice, and began to read Thomas Merton, Lao Tzu, Theresa of Avila, Buddhist scriptures, Martin Buber, Erich Fromm, Rollo May, Allen Watts, Sufi, Hindu, Christian, Jewish and Native American mystics. It seemed clear to me that they were all asking the same questions, and that, in their own way, each had found some sort of answer.

In the winter of 2001, not long after my wife Amanda and I learned that our oldest daughter had cystic fibrosis, we made (along with my mother, another avid golfer who still breaks 100 at age 82) a trip south to escape the cold and snow and our worries. During that trip, we stayed at some of the golf courses mentioned in Golfing with God, visited the famed Augusta National, wrestled with the question of why children suffer. I tried to put all my own questioning into the book, all my ideas about meaning and purpose, all my love of golf, people, and life. And, because it seems to me that the spiritual drama isn’t a maudlin thing, I tried to make it funny. The book is irreverent in places, too, but, I hope, in a playful way. I don’t know if the “sacred architecture” described in Golfing with God bears any resemblance to the way things are actually designed, but the mystics of every tradition all seem to be seeing the same world in their visions, and their descriptions ring true to me.

It also seems true to me that golf, that foolish-looking game, holds a secret within it, a mysterious series of life lessons. All you have to do is devote yourself to the game, face the humiliations square-on, laugh sometimes, and, like life, golf gradually makes you grow up.

About the author

Roland Merullo, a critically acclaimed novelist and golfing aficionado, is the author of the Revere Beach Trilogy, three novels about growing up in a tight-knit community outside Boston, as well as Passion for Golf: In Pursuit of the Innermost Game. He lives with his wife and daughters in Massachusetts.