Essay on Human Body Flaws

What Would I Change If I Could?

May 8, 2018

Human Errors and its author Nathan Lents

I recently sat for an interview for an upcoming BBC documentary about redesigning the human body. This interesting premise got me thinking about what I might change in the human body if I could. It wouldn’t be a short list.

I’m not talking about getting a flatter stomach, bigger biceps, or less gray around my temples. The human body is littered with imperfections that we all share, little quirks and glitches that serve to remind us that we’re a part of nature, not apart from nature, and that evolution does not create perfection. In fact, one of the questions the interviewer posed to me was, “If evolution could have designed a perfect body, what would it look like?” “No such thing!” was my immediate response.

Imperfection is the essence of nature. There is no finished product, no gold standard. Evolution is messy and aimless and our bodies reflect that. Even if you perform a thought experiment and imagine a perfectly adapted species that escapes every predator, defeats every infection, and finds every piece of food that it seeks, how long before it has eaten everything there is and is left to wallow in starvation? One of Charles Darwin’s essential observations was that all species overproduce offspring knowing that most individuals will succumb before reproducing. Life is a constant struggle and it couldn’t be any other way.

But since I’m a dreamer, and I know I’m not the only one, it’s fun to speculate about some of our little imperfections that it would be nice to correct.

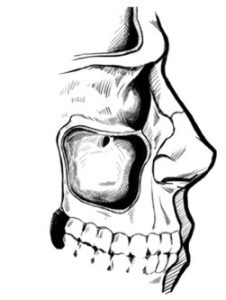

Since, like many of you, I have a little sniffle right now, let’s start with the nasal cavities. Few people realize what a mess our nasal sinuses are. Scratch that. Many people are intimately aware of the wretched state of their sinuses, but few are aware of the silly reason why. Our nasal cavities are constantly making mucus to help trap particles, but this mucus must be kept flowing and collected for disposal. It turns out that the mucus drainage point of the largest nasal cavity, the one right behind your cheek bones, is placed at the top of the chamber, rather than the bottom. If it weren’t for the hard work of the hair-like microscopic cilia, constantly propelling the mucus upward, there would be no drainage in this cavity whatsoever, at least not while we’re standing or sitting.

From Human Errors (Lents), illustration by Donald Ganley

How could evolution have made this big of a goof? And do other animals have this silly arrangement too? The answer to the second question is: definitely not. Neither dogs nor cats nor any of our ape relatives get colds and sinus infections as often as we do. Not even close. This is because they all have nasal sinuses that drain properly, working with gravity to keep the mucus flowing. The cavities themselves are important, of course, for warming and humidifying the air headed down to the lungs and for filtering out various muck, such as pollen and smog. The human sinuses can often do the job okay, but when an infection is brewing or we get hit with a heavy load of allergens, things get sticky — literally — and the cilia cannot keep up since they must fight gravity to do so.

Imperfection is the essence of nature.

But how did this happen in the first place? To answer that question, we have to go way back to the origin of mammals, some hundred million years ago. Among vertebrates, mammals have many distinct features, including a keen sense of smell. The earliest mammals evolved from reptiles that had long snouts. While we can’t know for sure, it’s likely these cynodonts developed the long snouts for the same reason that most mammals have them now, to give space for huge, air-filled cavities — the nasal sinuses — in which they can pack millions upon millions of olfactory receptors. These olfactory receptors are what give animals like wolves and dogs their incredibly sensitive and discriminating snouts.

Image credit: Nadine Herbst, Pixabay

Some mammals have moved away from the ancestral reliance on olfaction and instead invested in other senses, such as vision. Our own order, Primates, is just one example. Early primates smushed in the long snout that was obstructing the view from their forward-facing, binocular vision, which was getting better and better as trichromacy evolved, giving the ability to see a far richer array of colors. With the reduction of the snout came reduction of the sinus cavities. This process continued as apes evolved from primates and hominins evolved from apes. Humans have the flattest faces of all primates and the most reduced nasal sinuses.

Each primate species dealt with the reduction of the nasal cavities in its own way. In chimps, the maxillary sinuses are thinner and more horizontal than ours and the drainage point is near the bottom, where you’d expect. Orangutans ditched two of the four nasal sinus chambers altogether. Humans got the worst of it, by far. The drain pipes of the maxillary sinuses grew skinnier and skinnier, and, to make a bad situation worse, got stuck at the top of the chamber rather than at the bottom. If there are advantages to this odd arrangement, I have no idea what they might be, but there are certainly costs. In fact, most of the colds you’ve had in your lifetime, and those you will get, were probably due to your poorly designed maxillary sinuses.

So nearing the end of this year’s cold and flu season, I’d rank that near the top of any list of things I’d like to change about the human body.

Another thing I would change if I could is the shape of my eyeballs. In every medical textbook, we are treated to a beautiful drawing of a model eye, with a lens that focuses light perfectly onto our retina in the back. But in my eyes, that’s not at all what happens. My eyeballs are built too long. The lens does a fine job of focusing the light, but the light comes into focus somewhere in the middle of my liquid-filled eyes and there’s still a ways to go before the light reaches the retina. So what happens? The image goes out of focus again and the result is that my vision is blurry. Very blurry. My eyesight is somewhere around 20/420, which means I can’t see much past an arm’s length. I am entirely reliant on corrective lenses for even the most basic functions of life.

I am not a special case. The majority of the world has eyeballs that are either too long, like mine, or too short. Around 40% of the population of Europe and North America rely on corrective lenses, but in Asia, where the majority of our species lives, the figure is 75%. How can 20/20 vision be considered “normal” when most people don’t have it?

And that’s just talking about the percentage of people who need glasses from a young age. If we include those who lose their ability to focus on near objects after the age of 50, the figure approaches 100%. Almost everyone in the world needs reading glasses eventually. This flaw is for an entirely different reason. While the eyeball defect that requires us to get glasses when we’re young is caused by misshapen eyes, the need for reading glasses later in life is due the gradual hardening of the lens of the eye, making it difficult, and eventually impossible, for the ciliary muscles to bend the lens and focus on near objects. This is appropriately called presbyopia, literally, old man sight.

So those are two big flaws, right in our faces, that I would love to correct if I could. A little further up, we find a brain that is prone to all kinds of biases and miscalculations. And a little further down, we find a throat that was designed, quite incredibly, to convey both food and air through the same narrow tube. If we were to design the body from scratch, no sane person would design our throats in this way. But evolution doesn’t make designs. Our bodies are the result of the random forces of mutation and selection, making tiny tweaks and tugs along an aimless path toward… nothing in particular.

These are just a couple of the flaws in our heads and necks. Don’t get me started on all the poor design we find below the neck…