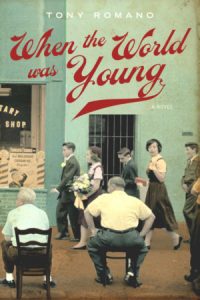

Chicago Sun Times Interview

Chicago Sun Times spoke with Tony Romano about his debut novel

Italian takeout

Tony Romano’s leaves out the stereotypes in his look at the lives and loves of immigrant families

By Stefano Esposito

May 20, 2007

Much of Romano’s Italian-American family tale sizzles in1950s Chicago with all the fiery heat of a serving of pasta all’arrabbiata, a chili pepper-spiced southern Italian dish.

But I found myself sitting down in early May with a soft-spoken, unassuming author, sipping lemonade on his suburban Glen Ellyn deck as we looked out onto an immaculate lawn and he fretted over the carpenter bees boring into his deck rails.

No Cousin Nunzio lurking nearby, cracking his knuckles, ready to smack a reporter who says he doesn’t like the book.

No Mama Romano in the kitchen, wiping her brow with one hand while the stubby fingers of the other peel garlic bulbs for the spaghetti sauce.

And you won’t find the like in Romano’s book, either, even though some of the overbearing, mouthy characters and Old World vs. New World themes will seem familiar.

Romano — who teaches high school English and psychology, and came to Chicago from Italy as an infant — was careful to avoid obvious Italian-American cliches. Maybe he was a little too careful. Among his editor’s suggestions: A little bit more Italian cooking. Romano obliged her, but he also made sure it helped develop the plot.

“Even the sex, I hope, is done tastefully and it’s not gratuitous,” Romano said, adding that there’s no “throbbing and pulsating.”

The book is about the Peccatori family, who live on one floor of a brownstone at Grand and Ashland.

The father, Agostino, is a philandering middle-age tailor with thinning hair whose life’s course was set at age 12, when he watched an Italian clothes maker fitting a woman for a dress: “He guided her to the back and I imagined all the measurements being taken. I could see those thick fingers pressing down the measuring tape along her thigh,” Agostino tells his brother Vince. “… That was the day I decided I would be a tailor.”

To which his brother adds: “That was the day we should have sewn your dick to your pants.”

There’s Agostino’s wife, Angela Rosa, who sometimes feels like the “dust that collects at the tops of doors,” and deals with her husband’s infidelity and loneliness by daydreaming about the neighborhood butcher: “She admired the fluid efficiency of those hands, how they could instantly calibrate the force needed to split bone or shave fat or just wrap a square of waxy white paper around a meaty steak in four sharp tucks that came away so clean you could almost slip the package in your purse.”

And there’s Santo, the oldest son, who at 18, touchingly still yearns for a lost closeness with his father. Santo both admires and loathes his father’s way with women. And he spends much of the book struggling nobly, but awkwardly, to prove that he isn’t merely a carbon copy of Papa.

The complexities and mysteries of familial bonds are brought into sharp, agonizing focus when the baby of the family, Benito, suddenly gets sick and dies. For a stretch in the book, the crushing pain of loss threatens to overwhelm the story, but then Romano’s tale emerges into surprising and satisfying territory. This includes a wonderfully disturbing scene in Italy that feels like something out of the cult horror movie “Rosemary’s Baby.” To say much more, would give away the plot.

Romano is clearly thrilled that his book is about to appear on bookshelves. He finished it in 2000, and during the next five years, he became an “expert on rejection.”

“I was pretty much gonna give up,” he recalled. “I was at a point where I thought, maybe it’s just not that good. Maybe I’m fooling myself.”

But then in December 2005 he got a call from an agent at HarperCollins, who loved the story.

“It was just a thrill,” Romano said of that conversation. “I couldn’t even breathe.”

Romano doesn’t have a particular audience in mind, but he certainly wouldn’t complain if some of the guys from his old neighborhood – the ones who sat outside in the warm weather, drinking shots and reminiscing about the old country, showed up at a book signing.

“I feel like I’m giving voice to those people who would never write a book, maybe even never read a book,” Romano said. “I just loved being around those kinds of people, who just seemed natural to me. They’re not trying to analyze everything; they are just living their lives.”

Stefano Esposito is a Sun-Times staff writer.