Book Group Guide

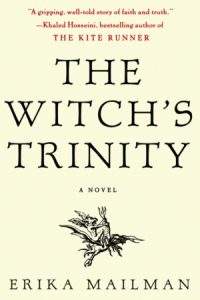

This reader’s guide is intended as a starting point for your discussion of Erika Mailman’s thought-provoking and powerful The Witch’s Trinity.

Questions

1. Before the famine, Tierkinddorf was a close-knit community where families lived side by side for generations. In light of this, why do you think the villagers were so willing to accept that one of their own was in league with the devil? Consider the very human need to have a scapegoat in difficult times. Why does having someone to blame for our woes seem to lessen them?

2. Describe Güde’s life. What is her position in the village? At home? On page 9, Jost admonishes his wife for treating his mother harshly but then leaves before making sure the fight is over; as a result, Irmeltrud sets Güde out to beg for her food. What does their treatment of the old woman say about them?

3. On the night that Güde’s daughter-in-law throws her out of the house, she wanders in the woods searching for Jost. Why is Güde afraid of the forest? What does it represent? Terrified and frozen, Güde believes she meets the devil and his followers there; she is tempted to sign his book in exchange for food. Does she do it? Is the whole event the work of an age-addled mind, or true evil?

4. Why does Irmeltrud hate Güde? Do you think her feelings toward her mother-in-law would have been different in a more plentiful time?

5. On page 49, Irmeltrud tells a neighbor that although Künne’s suffering at the hands of the friar didn’t put soup in her mouth, it did fill her somehow. What is Güde’s reaction to this statement? What does Irmeltrud mean by this? Why might Künne’s suffering make her feel better?

6. Jost puts himself in considerable danger with his defense of Künne, his mother’s oldest friend, at her trial. Why does he do this? What do his actions reveal about him? How does Künne try to help Güde before she is burned at the stake as a witch? Does it work?

7. Is Jost a good son?

8. 8. Why does Jost refuse to gather wood for the fire meant to kill Künne even though he knew food for his family would be the reward? Why is Irmeltrud eager to do the task? Do they both have valid reasons? Güde is horrified when she learns of her family’s involvement but eats the meat her daughter-in-law’s treachery earns them. On page 99, she says, “Hunger has turned me into an animal.” How are these words significant in light of the events in The Witch’s Trinity? What other characters in this book could have rightly said the same of themselves?

9. After Künne’s silent death fails to convince the friar that the devil is gone from Tierkinddorf, Güde considers killing herself (page 127). In her position, what would you have done?

10. Why does Irmeltrud accuse her mother-in-law of witchcraft? What does she have to gain in doing so? Do you think she really believes that Güde is a witch? Why does the friar begin to suspect Irmeltrud of witchcraft?

11. Imprisoned and awaiting trial, what is Güde’s reaction when Irmeltrud is tossed into jail as well? Did you think that this shared trial would bring the two closer together? Hidden in her skirt, Güde has two of the Pillen she gave to deaden Künne’s pain. Does she plan to share them with her daughterin-law? Given the choice, would you have shared with Irmeltrud? Does choosing not to share bring you to her level of cruelty?

12. As the oldest woman in the village, Güde has seen everything—and most everyone—she loves die before she istried and convicted of witchcraft. What memories comfort her through her ordeal? Is she afraid of death? What is the one thing she wants most before she dies, and why?

13. The witch trials in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible represent the hunt for Communists led by Senator Joseph Mc-Carthy in the 1950s. Is there a similar hidden meaning of the trials in The Witch’s Trinity? Consider who is accused and the general mood of the village before and during the trials as part of your answer.

14. During her trial on page 192, Güde accuses Herr Kueper, the man who accused her of souring a pail of milk. Why does she do it? She also confesses to crimes she did not commit. Why would an innocent person take responsibility for things she did not do? In her position would you admit you were a witch in hopes of getting a reprieve or even just a quicker death? Or would you maintain your innocence at any cost?

15. How does Güde’s granddaughter, Alke, become involved in the trial? How does Güde save her from being tried for witchcraft? Why does Irmeltrud suddenly join forces with Güde?

16. What saves Güde and Irmeltrud from the fire? Who is the woman that the hunting party brings back with them from the woods? Why is she familiar to Güde? What is the old woman’s reaction to seeing the other woman caged?

17. What happens to the friar? Would you consider his end to be justly deserved? What happens in the village afterward? Does it matter if the people are sorry or regretful considering what happened to the women they condemned?

18. What happens to Güde at the end of the novel? Are her memories of the past forever tarnished by the trials? How does having her granddaughter with her help her to live in the present? Both Güde and Alke refuse to see Irmeltrud again after the trial—why? Would you be able to forgive her? Would you be able to forgive any of those involved?