Book Group Guide

Introduction

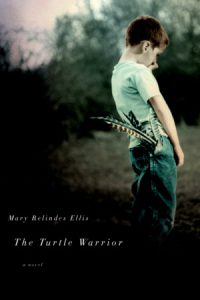

Mary Relindes Ellis’s extraordinary first novel, THE TURTLE WARRIOR, exhibits a depth and range rare in contemporary fiction. Set in rural northern Wisconsin, the story ranges over the Vietnam War, World War II, and most important the vast and unsettled terrain of the human heart.

From the opening scene, in which two boys stuff firecrackers into a snapping turtle’s mouth, to vivid depictions of a man who abuses his wife and children, to the searing portrayal of the wholesale carnage of Vietnam, THE TURTLE WARRIOR is steeped in violence. Indeed, violence is the vortex that spins at the center of the Lucas family. The father, John Lucas, is a failed farmer and mean drunk who beats his wife, Claire, and abuses his youngest son, Bill. Bill’s brother, James, a reckless and defiant teenager, has his own mean streak, and when he decides to enlist in the Marines to fight in Vietnam, it is both to escape an intolerable home life and to humiliate his father, who falsely claims to be a World War II hero. Left alone with John Lucas, Bill and Claire suffer the full force of his rage. They are plunged into a nightmare world in which Claire slowly descends into what she feels is insanity, and Bill, after his father’s sudden death, begins to drink himself into oblivion. Their neighbors, Ernie and Rosemary, and their unusual dog, Angel, offer the Lucas family their only contact with a normal life and with the warmth and love that might save them.

With a sure sense of the textures and rhythms of rural life, and an equally firm grasp of the interior landscape of her characters, Mary Relindes Ellis dramatizes the many ways that violence and abuse cycle through families and threaten to utterly extinguish the human spirit. But what she affirms most convincingly, in writing of remarkable emotional nuance, is love’s power to transcend and transform that suffering into joy.

A Conversation with Mary Relindes Ellis

How did the characters of THE TURTLE WARRIOR come to you? Are they closely or loosely based on people in your own life?

I know most readers assume that first novels are considered to be largely autobiographical, and it is true in that the turtle scene is from an event in my childhood. I know these characters because I built them from experiences and stories and people I knew from childhood. I created Bill out of a sense of my own experiences as a tomboy and from having had brothers. But in writing a novel, and this one took many years because of personal interruptions in my career as a writer, the characters became themselves. I think of them in this way: They became themselves just as children may be born to a specific set of parents but will not entirely become their parents because of environmental influences and factors, the generations that separate them, the cultures they discover for themselves, and so on. They are unique people and not clones of their parents. My characters often surprise me and still surprise me. They are a blend of fiction, some fact, history, and the subconscious. I did grow up, contrary to the myth about the Midwest, with diversity in terms of ethnicity. For instance, as a child I had several babysitters, all of them from a different ethnic group: Italian, Finnish, German, Croatian, Norwegian, Swedish, French, Czech, and English/Irish. My mother had a friend, Alice, who was Ojibwe. As a teenager I cleaned cabins at a resort where the husband was Czech and his wife was originally from Alabama.

How did growing up in northern Wisconsin influence your sensibility as a writer in general and your writing of THE TURTLE WARRIOR in particular?

I think the culture of northern Wisconsin, more so in my youth, had activities different from today, and because it was so rural, time did move slowly. I was a child of a large Catholic family, and I also grew up knowing many elderly people and having older relatives. When we lived on our farm in Glidden, we played outside in every season regardless of the weather (except for extreme storm conditions). Nearly every kid in my family fished or was taught to hunt, and even if the girls didn’t hunt, they all had some experience with firing a rifle or shotgun. While hunting was a sport, it still retained that serious kernel of necessity. That is, I don’t remember anyone wasting game or venison-it all went into the freezer or was canned, and this was considered an annual food source.

I had extraordinary freedom and space as a child, and even after we moved forty miles away to live in a town, I still had the freedom to go on bicycle rides that could be ten miles or more. This sense of freedom and independence made me treasure the immediate world around me. Some of my happiest moments have been spent outdoors. It would seem shocking now to many parents, especially in our extreme fear and paranoia about child snatching and molestation, but my mother had seven children and many other difficulties weighing on her mind. She was of a generation where it was natural for your children, after their chores were done, to go outside and play without much supervision. We happened to have a big “outside.” We were naïve in the way that many rural children were then about urban life, but we were also very savvy about reading people and were experienced in our environment. My mother warned us about talking to strangers. I’m not sure how we learned how to make ourselves invisible, and I don’t remember it as a reaction to fear but just as a natural precaution. For instance, walking on the dirt road down to the Chippewa River. If we heard a car coming and couldn’t quite identify it (you can laugh but we did know some of our neighbor’s vehicles just by the sound they made-and of course a tractor was a “safe” sound), we either hid in the ditch if it was deep enough and grassy enough or we moved inside the first tier of trees alongside the road and waited for the car to pass. We generally did that when it was only two or three of us-if all my brothers and sisters were together, we were a large enough group so that we didn’t feel the need to hide.

We did not go to movies regularly as the movie theater was twenty-five miles away in Park Falls and it was a rare treat. We played card games, board games like Monopoly, or when we were in town, we were at my Aunt Martha’s general store. Shopping was not considered a form of recreation. Adults who had suffered through the Great Depression had a very strong work ethic, and people who frowned upon waste surrounded me. Extreme materialism toward children still wasn’t the rule of the day, and most people I knew simply didn’t have that kind of money. Mostly we just played outside, exploring, swimming, and visiting with neighbors. We did not expect adults to “play” with us, although we certainly had wonderful times with some relatives and family friends, listening to family stories or political discussions. What the adults did most was read to us, and we loved being read to. One of our most beloved babysitters, Tillie Henthorne, knew that if she sat on the couch with a few books, she could almost get all seven kids to sit quietly and listen (in fact, the actress Joan Plowright reminds me vividly of Tillie and even has the same voice). Although our TV didn’t often work at that time, we always had music. My mother loved all kinds of music, although she was reared on mostly classical music. She made sure the stereo always worked, and so we grew up listening to music: swing, jazz, blues, Broadway musicals, classical, folk, and some country-western. We also grew up with a reverence for books and for reading. It stuns me to think about it because technology has moved so rapidly that thirty-six years ago feels more like double that to me. We did not have DVDs or VCRs or computers, we did not watch much television, and we did not have malls or stores to hang out in, or even money to travel beyond our state. Books, music, the outdoors, school, and community life, including church, became central for our education, our entertainment, and our need to escape.

The above shaped my sensibilities as a person and a writer, but I was also shaped by violence and by contradictions. I grew up with violence in my own home as well as witnessing or knowing about it in other people’s homes. I grew up seeing alcoholism all around me. I grew up with a culture that still considered it acceptable for a man to hit his wife, and for women and girls to be considered second-class. As a consequence, my mother and Great Aunt Martha lectured the girls in the family repeatedly about not getting married too young, about traveling and getting an education or trade, and about the seriousness of having children-especially if we had to raise our children alone because something “happened” to our husbands. Yet we were also raised with the bad woman/good woman dichotomy, or the virgin/whore syndrome, as it is also known. We were not supposed to have sexual freedom. And bizarrely, none of the girls in my family have a middle name because it was assumed we would take “Ellis” as our middle name when we got married. I recently took my mother’s first name, Relindes, as my middle name to honor her and to keep the name alive.

Another thing that has shaped me as a writer is the one thing that isn’t obvious. It appears to remain true of children raised in alcoholism and, often simultaneously, violence, in that those children learn to occupy themselves in isolation. Rather than being detrimental to me, I’ve turned this around into a skill. In fact, all my siblings treasure and need solitude, and I can bear being alone for long periods of time, which is invaluable to a writer. While some of my happiest moments came from being outside and exploring in the woods, I also experienced the treasured quiet of reading a book or just thinking and imagining.

You chose a very different path than what is currently considered the norm for many writers nowadays. That is, you do not have an MFA degree and did not attend workshops or literary conferences. Why is that?

The MFA degree, except at Iowa, was not as readily available when I graduated from college. And quite honestly, the thought didn’t cross my mind. I had a heavy load of student loans just from acquiring a BA, and I didn’t want to get more in debt, although I did consider getting a double Master’s degree in biology and English literature. I grew up in a family that cherished reading and books, and the notion of needing a degree or more than one degree to write was simply not a part of my family’s culture. You either became a reader and writer and just did it, or you didn’t. My Uncle Mel was a writer and journalist of the old school, and although I had almost no contact with him growing up because of geographical distance and a split in the family, the whole idea of toughing it out and booting yourself into the attic to write was a strong one in my family. The only writing courses I had in college were in writing poetry, and I consider that background essential. I never took a course in fiction or nonfiction writing. I think reading and writing poetry teaches a writer to pay attention to the individual impact of each word and the economy of words.

Writing came to me slowly. In reading literature from other countries and the literature of the United States as it was reflected in African American, Hispanic, Native American, and Asian American novels and poetry, I realized how important those childhood stories and experiences were to my identity as a person and a writer. I belonged to the United States of America, but quite honestly, I lived in a totally different region that was nearly its own country. It is still its own country. As much a misunderstood region as the South is misunderstood. We told and retold hilarious family stories and not so hilarious family history until they became our own mythology. I will never forget the first women’s studies course I took in literature. To read published writing in the voice most familiar to me-feminine-about subjects and perspectives that were not deemed classical and therefore “important” literature blew me away. Meridel Le Sueur wrote about the very things during the 1920s and 1930s that my Aunt Ruth had experienced as young woman in Minneapolis at that time. It shocked me to read those same stories that my Aunt Ruth had talked about. The poverty, the demeaning work of being a hotel maid, the fear that my aunt shared with so many other working women of being picked up for “loitering” on the street after hours (when the “girls” simply had a Friday night free, and after a cheap meal of chow mein, enjoyed a drink or two at a bar). Those women who were picked up as loiterers or vagrants were taken to Faribault, Minnesota, where “delinquent women” would be housed and often operated on for “appendicitis,” when in reality they were being sterilized. My aunt and her friends knew they had to appear as though they were headed toward a particular destination or when to get off the streets after-hours. It is an ugly part of that history. The female writers I read in college were writing more graphically, more openly about the violence and victimization of women and bringing that to light. They were also writing about things that should have been considered more important in literature and poetry: life-defining experiences such as motherhood or a being a daughter or sister. Or simply having the language of women matter. Such writing legitimized my own experience and allowed me to actually think that I could be a writer.

When I finally voiced my desire to be a writer to other writers of my own age, and then to a few faculty members, I was told that I had to go to New York to be a writer. I have nothing against New York, but the message was that I had to be “cleansed” of my Midwestern background in order to have anything valuable to say as a writer. Although the culture and place I grew up in was not always easy and sometimes frustrates me still, I recognized that it had a history and value of its own. I balked at the notion that I was “less than” because of where I was from. I had already felt discounted as a woman, but to also have my region and the land of my youth discounted was too much. My mother had once said that we needed to look at the people and history in our own backyard, so to speak. I had been steeped in Old World culture. I didn’t quite fit in that culture and I wanted something different. I wanted to know the literature of the Americas and the mythology that informed that literature. But when I told my mother that I wanted to be a writer, she cried. My mother cried, because in her experience, writing was a hard choice for a man to make, and even harder for a woman. It also frightened her. My mother loved reading and loved literature, but it is one thing to love it when the writer does not belong to your family. It is quite another to have the writer in your family. She was a very private person and treasured her privacy and solitude. We butted heads quite a bit. Nonetheless, my mother (she died in 1996) had a very strong influence on me, and although some of her messages contradicted each other, I learned a great deal from her.

She was right. It was hard. I was subject to family criticism and snide comments for years because I didn’t have the “right” relationships, didn’t get a high-paying job, didn’t own a home until I was in my late thirties, and didn’t have the material things that would signify what they considered success. I didn’t own a car for fifteen years when I lived in southeast Minneapolis. I took low-paying jobs so that I would have the time to write, but the writing came slowly. I did make poor personal choices that interrupted my writing, and yet they informed me as a writer. I never was very fond of the workshop form of writing classes. I preferred to have a few good mentors who could read my work and give it constructive criticism. And I consider reading as instruction in writing. I have had many teachers this way and many of them from vastly different backgrounds.

In THE TURTLE WARRIOR men and women appear to have very different ways of processing their emotions. Did you consciously set out to dramatize that difference?

It wasn’t until I was near the end of the novel that I became conscious of the difference between the means in which the men and the women processed their emotions in the novel. It is so ingrained in me and so ingrained in our culture. For instance, it never fails to amaze me how two strange women can meet and within minutes of talking become intimate enough to discuss some real pain or real struggles. I didn’t and I still don’t see most men doing that. So it was natural to me for Claire and Rosemary to speak in the first person. Most women can readily identify their emotions, and if they can’t, they often find some way to speak of it and someone to talk to. I can’t say much about the novel I am currently working on, but I will say that it involves that secret language of women, or you could say the language of the underprivileged. I may have grown up hearing English from both genders, but it was, in fact, like hearing two different languages. My mother didn’t have to say much, but her tone, her body language, her inflection, and the words she chose had a dramatically different impact, and it was true of her friends and the other women I knew growing up.

I was more conscious of the fact that Bill and Ernie needed to be in the third person because I often heard “men” in the third person. What surprised me was my creation of James after he is killed. I felt his death gave him the right or the freedom to speak in the first person. He has lost everything including his own life and so he has nothing to lose by being forthright and talking about his feelings. It is very tricky to write in the first person especially if it involves trauma or pain. As the writer, I had to let those characters speak and somewhat remove myself. In doing this, I took away the distance between the reader and Claire, Rosemary, and James. I became conscious of what I had done with the difference between the male and female narratives after I gave James his voice after his death. I am also aware that for some readers, particularly for male readers, this kind of intimacy on the page can be uncomfortable and even threatening. I knew I was going out on a limb doing it this way. Yet, for those readers who have never been in the military or had someone fight in a war, this is a way for them to know just how terrible it is to be a parent or wife or sibling in such a situation and then to see what you have dreaded for months pull into your driveway. I wanted those particular readers to feel as though they were standing right next to Claire Lucas. You think very differently about life and politics when that international conflict comes right to your door.

Most books that explore the abuse of children focus on abused girls. Why did you decide to tell the story of an abused boy?

I didn’t set out to tell the story of an abused boy per se. It happened in the course of my writing the novel and was based on some things I had learned.

I took quite a few women’s studies courses in college and read many abused women stories. I had grown up knowing I was vulnerable as a woman and that victimization toward girls was common. I grew up fearing rape and/or assault. I knew many girls and women who had been sexually abused as children or had experienced some kind of abuse as women. But as I reconnected with my second-oldest brother, and watched as he struggled to stay sober as a twenty-five-year-old, I became aware of how hard his struggle was-not necessarily harder than a woman’s struggle, but at the same time it was harder because he had trouble expressing his loneliness at having to do things by himself because most of his friends drank or drank socially. To be that young and completely sober was an oddity, and peer pressure is still immense at that age. I had been in a three-year relationship with a Native American man who was an alcoholic. He could only talk about the pain of his childhood when he was drunk: of being abandoned to a boarding school, of feeling lost, physically and culturally, and of the daily experience of racism. Simultaneously, while I was reading those women’s narratives about incest and abuse, I knew that male rapists or abusers often have childhoods in which they have been sexually molested. I wondered why that was never really openly discussed-the sexual abuse of boys.

So it came to me that many men live in a kind of tortured silence because they do not allow themselves or our culture does not allow them to speak of the abuse that may have happened to them. Men for so long were not taught to think about or identify emotions. Then add to that the culture of being privileged or considered “first.” Rather than an advantage, it suddenly becomes a wall and silences men who have been abused in childhood. It is common to think of the sexual victimization of girls and women because of the power differential, physically and culturally-women are perceived as helpless. When I was growing up, people worried about the safety of their daughters physically and sexually, but nobody really thought about or considered the sexual safety of their sons. Oddly enough as well, boys are granted a masculine status of power that they don’t really have; hence the subtle but damaging message is that they could have prevented what happened to them. Girls get this message often, too. People will say “she knew what she was doing” when, for instance, an eight-year-old girl is being flirtatious. A mature adult realizes that such flirtation is part of a growing psyche and a girl may have no idea of what she is projecting or imitating. But a predator can act on that behavior and use it as a defense in a court of law, which is hideous. Who is the adult and who is the child? It is a ridiculous notion. A girl child or a boy child simply does not have the power to physically or psychologically protect herself or himself from an abusive adult, particularly if that adult is a family member. It still remains a horrendous and criminal act toward children, but at least the silence is now being broken for boys and men. Yet for men of my generation and the generations before me, this was a devastating secret that is still hard to give voice to.

I think Vietnam veterans made enormous gains in breaking through that cultural silencing of male pain because of the kind of war Vietnam was, because those veterans had to really fight to get help for postwar traumatic stress syndrome and other war-related disabilities such as Agent Orange exposure. Unlike World War II veterans, they were not honored but were instead maligned because Vietnam was a terrible mistake. It was not their mistake, however. It was a Washington power play that fed on Cold War fears concerning communism that really masked business interests and imperialism. The public gradually learned more and more about the Vietnam experience, not just from scholars, but from fictional and nonfiction narratives, memoirs, and movies, written or created by Vietnam veterans. All those men were lied to, and those men who chose, instead of being drafted, to serve their country by taking the military route had their loyalty misused and manipulated. Those men are still suffering in numerous ways.

I’m not the kind of writer who can frame up the beginning, middle, or end and then fill in the gaps. I begin the story, and when the writing is really flowing, I seem to, and the story seems to, enter a state of grace where much is revealed. I did know as I created John Lucas that he would find a way to keep his second son “down” and powerless. As a woman I knew exactly what would be the worst way to cripple another human being. Bill is very different from his older brother. A very introspective child and not one given to open defiance, he copes with his father much like his mother copes with his father, through passive defense tactics. But he is too young to fight back against such overt and also covert violence. Keep in mind that what happened to Bill is unusual in terms of sexual abuse. I don’t want to state it here. I’d rather the reader thought about this.

Could you discuss the ways in which the turtle creation story is important to your novel?

Well, I love that particular creation myth, although it is not the creation myth of my own ethnic background and religion. I don’t like the scenario of one all-powerful being creating just two people, with the first being a man (Adam) and then creating a companion for that man by taking one of his ribs and fashioning a woman (Eve). I especially dislike the notion of original sin, in that Eve was responsible for getting them thrown out of the Garden and that baptism is to wash away that original sin, that original “female” sin. When I read Night Flying Woman: An Ojibway Narrative by Ignatia Broker, an Ojibwe elder who is now deceased, I remembered my mother’s comment about paying attention to the people and cultures in our own “backyard” (actually it is their ancestral backyard). I went to school with a few Ojibwe children who resided off the reservation and lived lives not unlike my own in that their parents worked and so on. We had interactions like most kids, but spirituality and religion were not topics for childhood discussion. For my siblings and me, church was a chore. I also didn’t contemplate racial difference so much because my mother was adamantly opposed to racism. It simply wasn’t acceptable to be racist in our household, and this was learned by example, not constant preaching.

We were to take people on an individual basis and avoid stereotyping. When I was in college, I read more narratives and history about the Ojibwe. When I came upon the turtle creation story, it really struck home. I had grown up loving turtles and was fascinated by snapping turtles because they appeared to be like dinosaurs and they were always very powerful. But I was also very moved by a creation story that did not involve retribution or sin or power in the way it is portrayed in Christianity. I love the idea that to build the earth, it took a community of species and a Sky Woman deity. She respects them and they respect her. Unlike the creation story of my own background, the Ojibwe story made a great deal more sense and was more realistic to me, especially given my rural background.

That myth became important to the novel because it is one of the few things that Ernie Morriseau retains of his Ojbwe culture and provides a strong link to his father. Although Ernie does not grow up on his father’s reservation, he retains that sense of community, of “fathering” children regardless of whether they are his own or not. This is not unique to Ojibwe or Native American culture. The modern nuclear family as it is called isn’t really a healthy family. To have extended family close by provides a child with a wealth of opportunity in seeking love and teaching from a variety of adults as well as cousins. Many immigrant families did have this. And in many small towns, at least in my youth, adults not related to me could still assume a community role. For instance, if I pulled a prank or did something that was wrong and a neighbor caught me, that neighbor had the social freedom to scold me for what I had done. It wasn’t discipline out of meanness, but that of an adult teaching a child that what they had done was wrong.

The turtle story illuminates the entire circle of life: that every part of creation, even the smallest thing (like muskrat), has a significant contribution. Although Bill’s natural reverence and caretaking of sick or orphaned animals is an act of one species caring for another, it is seen as a childhood concern. We had a maternal need to take care of sick, wounded, or orphaned animals, and it also allowed us to study those animals up close. But in the creation myth of Ernie’s culture, that reverence for animals is a very adult one. It means that human beings do not have dominion over the earth and other species but rather must interact with other species. It means that if you wantonly harm or destroy one part of the cycle of life, you can break the entire cycle. Hunting, if it is practiced with reverence and to fulfill a food need, is also part of that circle of life. Ernie Morriseau was of a generation of Native Americans that was expected to assimilate into white culture. He recognizes with some sadness, as so many people do when they get older, that what his father had told him in the way of stories had relevance and was not merely myth. It is a very private and personal history he shares with his father. A private spirituality. It is probably not a story he would have shared with James Lucas, and only after some prodding, does he share it with Bill when Bill is an adult.

Your novel does not participate in the ultra-hip, ironic self-consciousness that characterizes much postmodern fiction. How would you describe your relationship to the contemporary literary landscape?

I’m not sure I agree with that assessment of postmodern fiction, although I do agree that there is a lot of ultra-hip, ironic self-conscious fiction being published, and I am not a part of that and I doubt I will be. There are many writers still connected to that deeper vein of living that defies a label. Writers such as Toni Morrison, Michael Ondaatje, Russell Banks, Naomi Shihab Nye, W. S. Merwin, Wendell Berry, Barry Lopez, Linda Hogan, Louise Erdrich, Jamaica Kincaid, Alice Walker, Margaret Atwood, A. S. Byatt, Leslie Marmon Silko, Pat Barker, and so on. The Canadian poet Ann Michaels wrote an incredible novel, Fugitive Pieces, which covers a much-written-about subject-the Holocaust-and creates yet another story from that experience that is powerful, dark, lyrical, and mesmerizing, and shows the quiet perseverance of spirit.

I remember Tim O’Brien saying something to the effect that we are all dealt certain cards in life and his card was the Vietnam experience. I have several cards, one of them being the Vietnam experience as someone who had a brother in Vietnam. I grew up mainly with my mother’s side of the family, which was heavily German Catholic. My mother’s mother died when my mother was born, and so my Great Aunt Martha became the grandmother figure. I grew up hearing stories of the 1918 influenza epidemic (I had a another great aunt who survived the epidemic but was so weak that she contracted and died of diphtheria at the age of seventeen), the Great Depression, and the 1940s. I was not allowed to be self-centered, and although we were loved as children, we were certainly not indulged on the scale that later generations were, and boundaries between adults and children were more strictly enforced. I come from the northern middle of the United States, and it is true, time moved slower. I was raised to think about my place in the world, about being responsible and accountable, and with a sometimes-harsh code of conduct. Because of the necessary break in my family, when my mother defied the accepted status quo of being a battered woman and obtained a divorce, all of my siblings had a great deal of responsibility at an early age. We were not afforded the luxury of being self-indulgent, and of course growing up heavily Catholic, we received a huge dose of shame and guilt. I certainly didn’t grow up hip, although I tried to be hip and wore platform shoes, big hair, big earrings, and wild makeup in the 1970s. Part of that was defiance against that overriding cultural view of beauty as being blond and blue-eyed, which I was not. I went to high school with rural kids and town kids. I still don’t remember any of my classmates being “given” a car for their sixteenth birthday. The boys of course tried to gets cars as soon as possible, even if that meant piecing together a junker or what some people would call a ghetto cruiser. They worked jobs for that money or worked at home and were paid by their parents. But they earned it. Most of us, however, had to borrow the family car. Hence, I did not hang out at malls or have the money to spend that so many teenagers now have. I don’t know what it is like to grow up in a very urban area or a suburban area. I grew up with working-class people, and because of my mother’s job as a public-health nurse, seeing poverty and death. My older sisters in their youth were part of the 1960s and early-1970s social consciousness. My mother was a socially conscious person and believed in free thinking and independence. She always remained proud of what one visiting school psychologist said to her in amazement. The psychologist said, “I’ve never seen such a large family in which all of the children are nonconformists.” My mother always beamed when she told that story. She considered it quite an achievement that her children could think for themselves, even though at times it vexed her enormously.

I read all the time. I don’t read strictly fiction. I read history, nonfiction, some satire, poetry, literature from other countries, and I read writing by both men and women. So I’m not sure I can characterize the contemporary literary landscape with one label, although I understand the question. I do see popular literature that is very self-conscious and very “me”-oriented. But the definition of “hip” changes so rapidly. I wouldn’t want to be a prisoner of that.

There is a lesser-known literary landscape, and I’m aware of it because of living where I do and reading regional fiction and nonfiction of the Midwest and West. The Twin Cities (Minneapolis/St. Paul) have had a long history of literacy and literary tradition. In terms of writers and writing, it is a very supportive environment with many resources. The Twin Cities have some prestigious small presses that turn out exquisite writing that isn’t about being ironic, ultra-hip, or self-conscious. Life is complex, but if you live in a virtual reality, a material reality, and if you were to go strictly by the media, you might think that there are only two classes: the very wealthy and the comfortable middle class. The disadvantaged, the working poor, or even the dirt poor are with us every day but they are largely ignored or discounted. In the past three decades, the middle class has enjoyed material wealth like it never has before. I’m not sure it is such a good thing. It is true, the 1980s were the “me” generation and the 1990s were the “mine” generation, and that was and is reflected in literature being published. I was in the generation before all of that, and my mother believed strongly in JFK’s “ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” I still think Kennedy’s pronouncement is a strong one, but unfortunately it is an ideal that has become manipulated and misused. Maybe I’m not postmodern [laugh]. Maybe I’m still “modern.”

What writers have most influenced your own work?

Well, having an uncle who was a writer in the family was a strong message that it could be done, and I’ve read all of my Uncle Mel’s books. I can say without a doubt that Leslie Marmon Silko’s book Ceremony had a profound effect on me. I had at least four uncles in World War II, and although I didn’t grow up illegitimate or of mixed blood, I did grow up with the heavy prejudice against divorced and/or single mothers. I understood and understand the nature of despair. Silko’s book gave me a different perspective on “evil.” I bought the book, called in sick to my job, and stayed in bed and read that entire book in a day. And I’ve reread that novel at least eleven times, each time finding something else about it that gives me cause to stop and ponder. I loved Erdrich’s first book, Love Medicine, and laughed when reading it because I had grown up with so many of those same people. It was the same way when I read The Beans of Egypt, Maine by Carolyn Chute. Thomas King can write about the Native American experience with both seriousness and extraordinary humor-in other words, convey a more realistic picture of that life. Other writers that I read off the top of my list for pleasure and instruction are Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Margaret Atwood, Russell Banks, Jamaica Kincaid, Isabel Allende, Maxine Hong Kingston, Amy Tan, Jim Harrison, Tim O’Brien, Barry Lopez, Michael Ondaatje, Ursula Hegi, Andrea Barrett, Annie Proulx, Gabriel García Márquez, Thomas Sanchez-well, that list always grows and continues to get longer with new writers. But I also return to writers that I consider fundamental and very relevant to our times. Writers such as John Steinbeck, Flannery O’Connor, Carson McCullers, Frank Waters, Willa Cather, William Faulkner, Wallace Stegner, May Sarton, Meridel Le Sueur, Harper Lee, Margaret Walker, Langston Hughes, James Baldwin-that list goes on and on, too.

I also love poetry and try to read as much of it as I can, which isn’t as much as I would like. When I find I am stuck in writing, I will often stop and read poetry. Poetry helps me get my own imagery back and brings me back to the essence of the word. Two chapters of my book were published in Glimmer Train magazine as short stories, and one of them began with a centuries-old Japanese poem from an anonymous woman, and the other story began with a quote from “The Fifth Son” by Elie Wiesel. I love using a poem or a stanza from a poem as the imagery to start a story. I am mainly a prose writer, but I would like to get back to writing poetry. I consider poetry essential to the literary landscape and to life. I think poetry by its nature, even with the diversity of style, defies being ultra-hip.

Do you think of THE TURTLE WARRIOR as an antiwar novel or more broadly as an exploration of violence?

Both. The two are so intimately connected that I can’t separate them. There is “war” as we think of “war” in the global sense. And then there is that hidden, everyday “war.” If you think about how we train soldiers, especially those going into the Special Forces, we train them to attack, to kill. When we bring those soldiers back to the United States, we do not provide them with reverse training so that they can be phased back into the culture and not think in terms of “killing.” When a child is “trained” through being beaten, or watching his or her mother or siblings get physically beaten and verbally maligned, that child grows up with a very skewed view of the world, unless that child experienced some intervention or other examples to counteract what they lived with. If you add other variables such as racism or homophobia, it becomes an even more intense experience. For those children who grow up into violent adults, how do we bring them back? Prison statistics will tell you that most environmental damage of that kind creates a human being who cannot be brought back. My cousin, Barbara, who works in the Minnesota Corrections System, has said that most maximum-security inmates are missing either all three of the following necessities or at least two of them: family, education, and religion. In reading Emotional Intelligence by Daniel Goleman, the theory that trauma over time can actually change the brain’s chemistry so that the person affected is in a permanent fight-or-flight mode is a strong one. Battered women and war veterans can attest to that. It then supports one of our oldest truths. Violence begets violence. You can see it through the generations and cycles of violence in Ireland. To stop that process takes a nationwide effort to break that cycle, to raise children who are taught to think of resolving conflict through more peaceful means.

Discussion Questions

- Why has Mary Relindes Ellis chosen THE TURTLE WARRIOR as her title? In what ways is the snapping turtle, both literally and symbolically, important to the novel? Why would Bill call himself the “Turtle Warrior”? In what ways does he come out of his shell by the end of the book?

- In the novel’s opening chapter, Ernie reflects that “allowing words to go unspoken could cause not only harm to oneself but harm to another” (p. 5). His wife, Rosemary, says of him that “He deals with pain like most men, treating it as though it doesn’t exist and therefore cannot be talked about” (p. 204). At what crucial moments in the novel does the failure to speak, to communicate one’s deepest or most painful feelings, cause harm? Why would Ernie, particularly, feel such grief over words unspoken?

- Mary Relindes Ellis employs an unusual narrative strategy in THE TURTLE WARRIOR, retelling the same events from different points of view. How does this way of telling the story affect how we read the novel?

- Lieutenant Hildebrandt ceases to believe in God when he sees the horror of war in Vietnam. He feels the killing is for “nothing but old men’s dreams of winning the invisible. There were no holy wars. There was nothing but money and games and betrayal at the top” (p. 101). Is his view of war borne out in the novel itself? How do the other characters-Jimmy, Ernie, Rosemany, John Lucas’s father-feel about war? In what ways can the manner of Jimmy’s death be read as an indictment of war?

- Rosemary tells Ernie to “think of crying…as medicine. It feels bad now, but it will make you feel better in the long run” (p. 220). She also thinks that “It is those men who do not cry that are in danger and dangerous to hunt with” (p. 224). Why would the inability to cry make one dangerous? In what ways does the open expression of pain and grief save Billy and Ernie at the end of the novel?

- How would you explain the extreme violence-from John Lucas’s abuse of his wife and sons to the war in Vietnam-that occurs in THE TURTLE WARRIOR? What are the connections between violence in families and violence between nations?

- Claire asks, “What possesses a man to torture an area of the body meant for pleasure and for giving life? A sacred area. How could he do it to a little boy? His own son?” (p. 306). Why does John Lucas inflict such pain on his son? In what ways has his own father’s treatment of him led to this behavior? What enables Bill to break the cycle of abuse?

- In what ways is Claire’s predicament typical of women trapped in abusive relationships? What options does Claire have? Should she have left her husband? Why doesn’t she?

- Bill thinks that “people who were much loved and who died had a way of clinging. Rather than fade, they grew in another dimension” (p. 341). In what ways does Jimmy’s spirit “cling” to his family? At what crucial moments does he appear or communicate with the living? What effect do these communications have?

- When Bill starts reading again, he realizes that he “had forgotten the interior pleasure of sitting quietly and absorbing a story that lifted him effortlessly away from his own life and at the same time strangely affirmed that his own life was real to him” (p. 315). In what ways does reading THE TURTLE WARRIOR itself offer both an escape from, and a deeper connection with, one’s own life? In what ways is it diverting? In what ways does it explore the basic human dilemmas we all experience in one form or another?