The Story Behind the Book

When I began writing in the early 1980s, I was in my junior year of college. My mother said casually in what was a critical but unknown moment of my development as a writer that we should look at the diverse cultures in our own backyard, meaning a mix that included the Ojibwe and other Native Americans groups. It was then I slowly became aware that I was from a unique area of the United States and that its history had a definite impact on my family.

The country of my childhood was still filled with working class immigrants and with intense populations of Finns, Germans, Swedes, Poles, Croatians, Czechs, Slavs, some French, and the Ojibwe. These groups mixed only when absolutely necessary, maintaining for many decades, their own pockets of ethnicity and race.

Home for me was a small farm in a small town in northern Wisconsin. It is an area with a history of isolation. Wide scale cutting of enormous white pine at the end of the 1800s and into the early 1900s by lumber companies so decimated this northern landscape that when later asked about it, veterans from WWI could only describe it in terms of what they’d seen in France and Germany-land cratered and burned by bombs and generally ravaged of all its beauty.

We were a family of seven children and we attended the Catholic Church and school in our small community. At home the TV was frequently broken which ultimately proved to be fortunate: we often sat through long noontime Sunday dinners and listened to political debates between our mother and our great aunt or other relatives or friends that may have been visiting. In between the politics, they told and retold community gossip and family stories. Yet despite ingesting a heavy dose of German Catholicism we subconsciously believed in the religion of the woods and had an animistic sense of our surroundings. We were, as Wallace Stegner wrote, identifying himself thusly as a child on the last remains of the frontier in Canada, “sensuous savages.”

As a beginning writer I became aware that the women I grew up with told stories in a way that did not conform to the “classic” literature I had been exposed to; stories that were never simple but layered with sediments of experience and a language filled with nuance. These stories were like anthills in that they had many entrances, passages, and exits.

I not only wanted to write about where I was from but from a woman’s perspective. Yet when I began to write seriously, I was stunned to discover that I could not write about my own sex. Something blocked me. It nagged me on my walks to and from my secretarial jobs, work that I detested but needed so that I could write. The nagging feeling gradually metamorphosed so that it literally tagged after me every day.

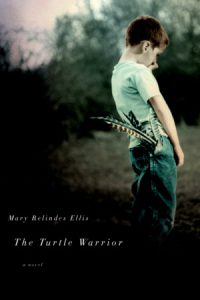

That feeling eventually took the form of a little boy.

So visceral was his presence that I often imagined him in my apartment with me, walking with me, eating with me but never talking. His presence was quiet and painful.

It was during this time that I was also trying to reconnect with my second oldest brother. My brother and I were never close. He occupied a strange niche in our family, being much revered as a boy but at times remaining invisible. As an adult this brother crawled out of a long and self-destructive period with drugs and alcohol to confront the demons of his life, one demon in particular being so secretive and taboo that it illuminated for me the difficulties of growing up a boy. Our father was an irresponsible and violent alcoholic who often had jobs that required commuting a fair distance and sometimes, spending days (and money) away from home; when my father was home and the turbulence inside the house became unbearable, we ran or hid or distracted ourselves in the nearby cedar swamps and pinewoods. Or we walked the three miles down to the Chippewa River. It was down at the river that we often saw snapping turtles, especially the large females that crawled out of the river in spring to deposit their eggs in the nearby sand banks.

One day the human violence in our lives and our sense of the naturally sacred collided. My oldest brother, sadly molded from birth into being a second version of our father, got drunk with another teenage boy and thinking it was great fun, captured a female snapping turtle by the river. He thrust some firecrackers into the snapper’s mouth and blew up her jaws. The turtle was mortally wounded and we were deeply disturbed, sensing that our brother had committed a wrong that had gone beyond the pale of drowning gophers out of their holes or even shooting robins and feral cats. Although we went to school with a small population of Ojibwe children, I did not know the Ojibwe creationist myth then. I didn’t have to. Snapping turtles are powerful and ancient, old beings that remain nearly untouched by evolution. They inspire awe in most children and sensitive adults. It was as though my brother had done something akin to torturing a much loved and venerated grandmother.

Not long after this incident, my battered mother finally divorced my father and we moved 40 miles away to another town to begin the difficult life of being seven children of a single parent whose income as a public health nurse was paltry. Angry about the divorce, angry at life, and suffering his own silenced pain, my oldest brother was goaded by my father’s repeated advice that he needed to serve his country. So he enlisted and was sent to Vietnam. He was already prepared for war even before he went through basic training, skilled in the ways of survival and in the nature of inflicting pain. He came home from Vietnam, a decorated soldier but an even more disturbed and destroyed man. It was not until that little boy who had come to inhabit me took me by the hand and led me back into it all that I realized being a boy in my family carried a terrible burden; that I was in the end blessed by being born a girl, blessed by my father’s indifference, although his treatment of my mother carried implications nonetheless.

I found my voice as a writer through this little boy. I recognized that my mother and so many other women who had loved and parented me were scarred veterans of a war that is thousands of years old, creating the vicious cultural cycle that never seems to end and that impacts every species on this planet. It is a knowledge and understanding that many children of battered women know intimately: war begins at home. Or more directly, terrorism begins at home. Its birth in our nuclear and extended human families does more than destroy humans; it destroys everything we need to live such as clean air, clean water, non-eroded soil, and habitats for other animals.

I have a quote from Thich Naht Hanh, the Vietnamese Buddhist monk who wrote Touching Peace: Practicing the Art of Mindful Living, taped to the windowsill in front of my typewriter.

We who have touched war have a duty to bring the truth about war to those who have not had a direct experience of it. We are the light at the tip of the candle. It is very hot, but it has the power to illuminate. We who were born from war know what it is. The war is in us, but it is also in everyone.

Every writer knows that worldly events grow from seeds in very small places, some of which are ignored. If I have, at times, felt silenced as a woman, I have felt equally silenced as a child born in a region of the United States cynically referred to as “flyover land” because it is dwarfed by the urban sophistication from the East and West Coasts. The Turtle Warrior is a work of fiction created from the layers of real life in that isolated region so full of amazing stories, and of women and children in that landscape who have been burned but who “are the light at the tip of the candle.” I sought to illuminate some of what has remained with me since being a girl: that children like animals, in an effort to survive, instinctively seek from their physical environment and from other beings what their own families cannot provide; that we can stop violence at the very beginning if we choose to; and that as the traditional Ojibwe have always known, wisdom and clarity can come from a turtle.