The Story Behind the Book

We used to spend our barefoot summer days plucking crawdads from the creek and walking down to the corner store for RC Colas. At the annual fireman’s picnic, the volunteers proudly wore their uniforms emblazoned with the slogan “Last of the Rebels” and pronounced that while Lee surrendered, Town Line never did.

It would have been impolitic to point out that indeed Town Line had surrendered, although not until 1946. It was then, in a publicity stunt involving everyone from then-current US President Dwight D. Eisenhower to soon-to-be-Batman-villain Cesar Romero that the Union was finally made whole by its reunification with this last holdout of Civil War secession, a Western New York hamlet fifteen miles from the Canadian border.

My family bought the oldest house in the little hamlet of Town Line in 1971, twenty five years after it had rejoined the Union. And although an occasional news crew would come out from Buffalo to do a quirky bit on the town’s claimed secession, we never heard the real story. It was never discussed in school, and the neighbors weren’t inclined to discuss the bizarre history with the strange Chinese-American family that had taken over the landmark house.

My family bought the oldest house in the little hamlet of Town Line in 1971, twenty five years after it had rejoined the Union. And although an occasional news crew would come out from Buffalo to do a quirky bit on the town’s claimed secession, we never heard the real story. It was never discussed in school, and the neighbors weren’t inclined to discuss the bizarre history with the strange Chinese-American family that had taken over the landmark house.

And though there were vague mentions of the Underground Railroad, no one could tell us the real purpose of the short tunnel dug into the wall of the house’s cellar.

I can’t recall ever actually climbing into that dark little space, or seeing any of my brothers try it either. But as a little boy, I’d stand and look at that hole and wonder about it.

Whenever I came up from that dark cellar, I’d shake its spell by pulling the rope that hung from the ceiling at the top of the stair, and the big brass bell in the house’s belfry would ring loud over the hamlet. We had been told they used the bells to call the slaves in.

It was only after I moved to Georgia that I understood how bizarre this all sounded. After listening to stories of family silver hidden and pilfered by rampaging Yankees, I would respond with my own tales of Yankee secession and Underground Railroad hidey holes and be met with looks of out and out disbelief. And so, I set out to document this Civil-War story in the era of Google.

At first, I found only bits and pieces: A New York Times piece about the town’s reunification vote and the publicity around it: A Buffalo Evening News piece hinting of Confederate sympathy, and a Courier Express quote from a local historian who talked of draft dodging and the shame that her family felt in the story.

And then one day I searched for my Town Line street address and found a picture of the old house and an oral history of the Willises, the family that had claim to the place.

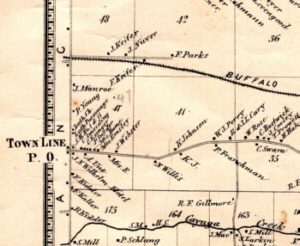

I found Nathan Willis, who came West from Vermont in 1811, claimed four hundred acres of wilderness, built the house, founded the town and had seventeen children. His name shows up in the political rolls, Whig, Freesoiler, Republican, Town Commissioner, Highway Superintendent, and County Commissioner. His was one of the earliest and most important names in the region.

I found the military records of his son Leander, the resignation letter that ended his month-long stint as an officer after recruiting twenty eight others to follow him in, and the letters his doctor sent detailing his deteriorating health, excusing him from his second tour, this time as a lieutenant among the US Colored Troops.

But the story that captured me was Nathan’s youngest daughter, Mary. In the stacks of the University of Buffalo, I found her name on a list of operators of Underground Railroad stations, and then again in two popular history books on the region. Then she appeared on a list of graduates of Alfred Select School, only the second college in the country to accept women. I tracked down a few of her descendants, and was given transcribed oral histories of escaped slaves tapping on windows during winter nights,

But the story that captured me was Nathan’s youngest daughter, Mary. In the stacks of the University of Buffalo, I found her name on a list of operators of Underground Railroad stations, and then again in two popular history books on the region. Then she appeared on a list of graduates of Alfred Select School, only the second college in the country to accept women. I tracked down a few of her descendants, and was given transcribed oral histories of escaped slaves tapping on windows during winter nights,  and pictures of Mary sitting on the front porch of my house.

and pictures of Mary sitting on the front porch of my house.

There was also the list of her children born after the war, with names like “Lincoln” and “Sherman” among them.

In 1913, when Mary Willis died in the house she’d been born in, she left a legacy unlike any other.

She was an abolitionist, a feminist and a unionist who spent her spent her entire life in a place that had seceded from the Union.

I think back to the years I spent as the only ethnic child in an otherwise entirely white school system and I understood why her story hooked me. Although I have no claim to her character or courage, I understood the isolation she must have felt in that place.

But Mary’s story threw light onto the ignored history of the region as well.

In a 1976 episode of Saturday Night Live, Chevy Chase famously joked that while smallpox had been wiped from the face of the earth, there had been a small outbreak in Buffalo, New York. Growing up in the countryside outside Buffalo, we were imbued with the sense that nothing important ever happened there. But during the years of the Civil War, Western New York was central to American history, and perhaps the most radical region in the country.

In the years leading up to the war, Frederick Douglass published his abolitionist paper out of a Rochester Church basement while Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony turned Seneca Falls into a hotbed of feminism. One hundred miles south of Buffalo, Edwin Drake struck black gold at Oil Creek, setting off the first oil rush in the nation. Even modern finance was born in Buffalo during the era, with the creation of modern American currency by Elbridge Spaulding and the beginning of modern credit through William Fargo.

The area had fueled so many doomsday cults, messianic sects, and new religions (Mormonism and Seventh Day Adventism the most well-known survivors), that one nineteenth century religious scholar labelled it “The Burned Over District”, saying that the constant revivalism had left no tinder behind. It is a term still widely used by social historians.

Even the little farming hamlet of Town Line was not immune to radicalism. Just south, over Cayuga Creek, lived the Community of True Faith, a German communist sect. They fled Western New York when the drums of the war and the swelling population became too much, moving West en masse to found what would become Iowa’s Amana Colonies.

Even the little farming hamlet of Town Line was not immune to radicalism. Just south, over Cayuga Creek, lived the Community of True Faith, a German communist sect. They fled Western New York when the drums of the war and the swelling population became too much, moving West en masse to found what would become Iowa’s Amana Colonies.

The town, and the Willis farm itself, were also touched by political greatness. The rail line that ran through the Willis farm conveyed Abraham Lincoln to Washington, and then, four years later, carried his funeral train as well.

Buffalo’s radicalism was shaped by its status as a gateway. On the Buffalo waterfront, everyone and everything from Europe and the Northeast would have to disembark and move from trains and canal packet boats to Great Lake steamers on their way west to the territories.

But the geography that was most central to Mary’s story was not that as gateway to the territories, but as the border to Canada.

In 1861, Canada was still part of Great Britain, and although the empire had abolished slavery long decades before, its cotton mill economy was driven by the slave plantations of the south. So whereas crossing the Niagara River was the last step to freedom for escaping slaves, they often found the climate there quite chilly even in the dog days of summer.

Civil War-era newspapers in Buffalo are rife with rumors of raids and attacks from guerrillas across the river, and there are many telegrams and letters from Union generals taking the threats quite seriously. Jacob Thompson, the inspiration for William Faulkner’s Old General Compson, was sent to Canada by Jefferson Davis to head up the Confederacy’s spying and sabotage effort’s on the Union’s northern border. He threaded the waters from Fort Erie to Toronto to Montreal and is believed to have been involved in the draft riots of New York and Vermont’s St. Albans raid. John Wilkes Booth made the trip up to Fort Erie to meet with him just months before assassinating Lincoln.

The most outlandish plot featured John Yates Beall. He and his friend John Wilkes Booth were there at Charles Town at the spiritual beginning of the war when militant abolitionist John Brown was hanged. He would fight briefly under Stonewall Jackson before becoming a privateer and raiding Union ships on the east coast and Great Lakes. Thompson, watching as Atlanta fell to Sherman, sent Beall on an impossible mission to free three thousand Confederate captives held on Johnson’s Island in Lake Erie, arm them, and turn them loose to burn Buffalo to the ground. The plan echoed John Brown’s, and failed similarly, with its main protagonist hanged.

The heart of The Hidden Light of Northern Fires, however, is not the grand sweep of history, but the story of those left out of it: a runaway slave, young men on opposite sides of a war, caught up in their own failings and the tragic consequences of them.

But in the story of Mary Wills we find a woman raised among ideas that are still considered radical today. In her life as an abolitionist, a feminist and daughter of pioneers, yearning to move on to the next frontier, yet called to stay and save her own postage stamp of history, we see the beginning of what would become twentieth century America.