The Story Behind the Book

Until a couple of years ago, I kept the depth of my addiction to Jane Austen largely to myself. Participating in walking tours of Jane Austen’s London and Bath with an anonymous group of tourists was about as public as I got. At the end of one such tour in London, I noticed that my watch was gone. Perhaps I’d been too distracted, not only by the various sites where Jane Austen slept, shopped, worshipped, and got published, but also by the tour guide, who was decked out in an empire-waisted gown, white gloves, and a plumed bonnet. Despite her outfit, or perhaps because of it, I still felt like I was searching for Austen’s world. It was one thing to hear about cobblestone streets with a depression in the center for water and refuse, or to imagine Elinor Dashwood rolling her eyes while Robert Ferrars bought customized bling where Gray’s of Sackville Street once stood. It was quite another to see past the determinedly modern façade of twenty-first-century London, which the guide’s Regency dress only underscored.

As I walked back to my hotel, annoyed about losing my watch and having to buy a new one, it occurred to me that perhaps my searchings were too literal. Perhaps I would get a new concept of time with my new watch. Perhaps I would get to the chronological essence of my book; namely, that time does not exist. Here I was, digging for the 200-year-old London under the modern metropolis, but if I could just stop thinking of time as time, it would rise up from beneath the veil.

And so, very gently, the world of my book began to reveal itself. Especially when I got to Bath, where I toured the ancient Roman bathing complex. Although accessible to me, the magnificent Roman baths had been hidden beneath the baths of Jane Austen’s time, which I could see from the windows of today’s Pump Room, the same Pump Room my twenty-first-century protagonist visited in 1813. That was as tangible a glimpse of timelessness as I could have imagined.

Despite my fascination (or let’s be honest, obsession) with all those period details, the truth is that Jane Austen does, in fact, transcend time. Her all-seeing, all-knowing, take-no-prisoners approach to the follies and flaws of human beings makes her books not only timeless, but almost eerily contemporary, despite the bonnets and balls and carriages. It is as if she were a modern-day psychotherapist with a wicked sense of humor who time-traveled back to the Regency and wrote novels about everyone who spent time on her couch.

Feeling self-important? Read Jane Austen. In the midst of an identity crisis? Perhaps, like me, you’ll find a little of yourself in all her heroines. Northanger Abbey’s Catherine Morland, who is addicted to scary novels, dancing, and old houses, reminds me of who I was when I lived in a crumbling Victorian that was said to be haunted, or when I could spend all night in after-hours clubs and still make it to work by 9. Sense and Sensibility’s Marianne Dashwood, she of the tear-rimmed eyes and self-destructive tendencies, is who I was when consuming little more than espresso, Big-Gulp-size vodka martinis, and American Spirits was my idea of post-break-up nourishment. Emma is who I am when I get lost in the land of running-your-life-is-so-much-better-than-looking-at-my-own. I still wish I were as eloquent a smart-ass as Pride and Prejudice’s Elizabeth Bennet, but the more I venture into the minefield of self-reflection, the more I appreciate Austen’s less incendiary heroines: the quietly steadfast Anne Eliot of Persuasion, and even the iconically timid Fanny Price of Mansfield Park, whom I used to dismiss as a prude.

There are other rewards in Austenland, not the least of which is that girl always gets boy. In fact, girl always marries boy. If you’re a single woman of no fortune, which is what I was when I first started reading Austen, it’s easy to get hooked.

Only six novels in my endless loop? No problem. A veritable banquet of movies offers its own set of pleasures, such as Colin Firth fencing in tight pants for the BBC’s 1996 Pride and Prejudice or MI-5’s Matthew MacFadyen channeling Heathcliff for the 2005 movie version. There’s even a Bollywood version featuring Lost’s swoon-worthy Naveen Andrews. If there were 50 adaptations of Pride and Prejudice, I’d see them all. I’d buy them all. I’d play them all till they started skipping and I had to buy a new one.

After all, I am insatiable.

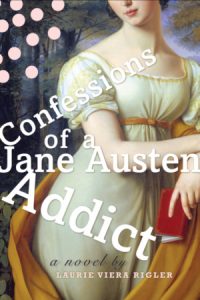

Which is why I started writing Confessions of a Jane Austen Addict. I could feed my cravings by creating a story of a twenty-first-century party girl who wakes up in the body and life of a woman in Jane Austen’s time. Now that’s what I call an identity crisis. That’s what I call the perfect excuse to immerse myself in the world of my favorite author.

And so I had gone to London, to Bath, to little country villages frozen in time, to the Assembly Rooms where Anne Eliot longed to catch Captain Wentworth’s eye. I went to conjure the past through the lens of my twenty-first-century protagonist’s mind.

Back home, I continued my research and stumbled across a bunch of Jane-centric groups and fansites on the Internet. (Apparently there were people as addicted to Austen as I.) The only group I joined was JASNA, the Jane Austen Society of North America. They were a scholarly group whose publications were food for my research. Or so I reasoned. So what if some of them liked to dress in period costumes for their annual Regency ball? Was that so wrong? Wouldn’t I like to don an empire-waisted muslin and learn English country dancing and pretend I was Gwyneth Paltrow dancing with Jeremy Northam? The very thought was enough to make me break out in a cold sweat. I could just see the look on the faces of my friends.

No, there was no reason for me to actually attend a JASNA meeting, not even when they blew into L.A. for their annual confab. Truth is, I was afraid of being in a room with other people who were not only as obsessed with Austen as I am, but who also had no problem labeling themselves as such. Might it not be like going to an AA meeting and admitting publicly I had a problem? Like my protagonist, I didn’t know if I was ready for that.

My husband, however, insisted I go. Alone.

After willing myself through the glass doors of the Biltmore Hotel in downtown L.A. and down the grand columned and chandeliered hallway, I made my way to the JASNA registration table. The women at the table were all giddy about BB King, who had apparently just passed by, caught sight of the sign and said, “Jane Austen! I love Jane Austen!” Thrilled, they gave him a tote bag.

Picturing the blues legend carrying around a canary yellow bag emblazoned with the JASNA acronym, it suddenly hit me: If BB King could love Jane Austen publicly, couldn’t I?