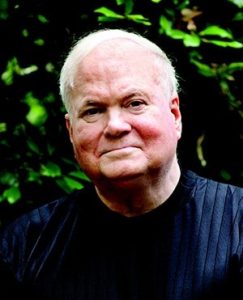

Remembering Pat Conroy – A Brief Biography

Pat Conroy, born in Atlanta in 1945, was the first of seven children of a young Marine officer from Chicago and a Southern beauty from Alabama, to whom Pat often credits for his love of language. The Conroys moved frequently to military bases throughout the South, and Conroy eventually attended The Citadel, a military college in Charleston,  South Carolina. Conroy often joked that a military school was an unconventional choice for someone who dreamed of being a writer, but, in fact, he found a number of deeply supportive faculty there, and Conroy’s first book, The Boo (1970), is a tribute to Lt. Col. Thomas Nugent Courvoisie, who served as a mentor to many Citadel cadets.

South Carolina. Conroy often joked that a military school was an unconventional choice for someone who dreamed of being a writer, but, in fact, he found a number of deeply supportive faculty there, and Conroy’s first book, The Boo (1970), is a tribute to Lt. Col. Thomas Nugent Courvoisie, who served as a mentor to many Citadel cadets.

Following graduation, Conroy taught English and psychology at Beaufort High School, his alma mater, and in 1969 he took a job teaching underprivileged children in a one-room schoolhouse on Daufuskie, a small island about three miles off the South Carolina mainland. Conroy’s year on Daufuskie was one of great change. That fall, he married Barbara Bolling Jones, a young Vietnam widow with two daughters, Jessica and Melissa, whom Conroy adopted. They would welcome a third daughter, Megan, the following year. He fell in love, too, with his students on the island, and was alternately energized by the challenges of teaching and enraged by the ways that the children had been neglected by the school system. After just a year of teaching on Daufuskie, Conroy was fired for his unconventional teaching practices, including his refusal to allow corporal punishment of his students, and for his clashes with the school’s administration.

Conroy wrote about his experiences that year in a memoir, The Water is Wide, which was published in 1972 and was recognized with an award from the National Education Association for its unflinching depiction of institutionalized racism in the public school system. In 1974, the book reached wider audiences when it was adapted as a film, Conrack, directed by Martin Ritt and starring Jon Voight, and these successes allowed Conroy to dedicate himself to writing as a full-time occupation. Although his teaching career was officially over, Conroy’s loyalties remained with those still in the classroom: throughout his career, he regularly sang the praises of his beloved high school and Citadel teachers, and he was always quick to assist teachers in any way he could, from meeting with classes to defending teachers in debates over censorship.

Conroy wrote about his experiences that year in a memoir, The Water is Wide, which was published in 1972 and was recognized with an award from the National Education Association for its unflinching depiction of institutionalized racism in the public school system. In 1974, the book reached wider audiences when it was adapted as a film, Conrack, directed by Martin Ritt and starring Jon Voight, and these successes allowed Conroy to dedicate himself to writing as a full-time occupation. Although his teaching career was officially over, Conroy’s loyalties remained with those still in the classroom: throughout his career, he regularly sang the praises of his beloved high school and Citadel teachers, and he was always quick to assist teachers in any way he could, from meeting with classes to defending teachers in debates over censorship.

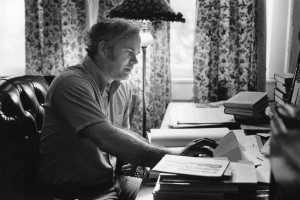

In 1973, the Conroys moved to Atlanta, where Pat wrote The Great Santini, published in 1976. The novel, which was later made into a film starring Robert Duvall, is grounded in Pat’s own childhood, particularly his difficult relationship with his father, a fighter pilot who regularly beat his wife and children. The publication of a book that so painfully exposed his family’s secret brought Conroy a period of tremendous personal desolation, and this crisis contributed not only to his divorce but to the divorce of his parents: his mother presented a copy of The Great Santini to the judge as “evidence” in divorce proceedings against his father.

The Citadel became the subject of his next novel, The Lords of Discipline, which was published in 1980 and was the third of Conroy’s books to be adapted as a film. In keeping with the themes of his previous work, the novel looks beyond a carefully constructed façade—in this case, that of a southern military institute—to expose the violence and hypocrisy that lie beneath it.

Conroy remarried and moved from Atlanta to Rome, where his fourth daughter, Susannah, was born. It was here that he began to work in earnest on The Prince of Tides, which, when published in 1986, became his most successful book. Reviewers immediately acknowledged Conroy as a master storyteller and a poetic and gifted prose stylist. Readers were immediately and absolutely devoted to the book: in fact, there are a remarkable five million copies in print. In 1991, The Prince of Tides was released as a film by actor/director/producer Barbara Streisand, and Conroy received an Oscar nod for his work in adapting the novel for film.Beach Music (1995), Conroy’s sixth book, is the story of Jack McCall, an American who moves to Rome to escape the trauma and painful memory of his young wife’s suicidal leap off a bridge in South Carolina. The novel is wide-ranging in its historical and geographical scope, and in its treatment of the Holocaust, Russian pogroms, and southern poverty, among other themes; it is generally recognized as Conroy’s ambitious—and perhaps darkest—work. Indeed, the writing of Beach Music, along with the suicide of his youngest brother and the end of his second marriage, triggered the most severe of what Conroy has termed his “great breakdowns.”

Conroy’s marriage to the novelist Cassandra King in 1998 represented a shift in his personal life, and, more subtly, in his work. His memoir My Losing Season (2002) allowed Conroy to reconnect with teammates as he sought to recreate his final season on the Citadel basketball team, and the book functions, in part, as a meditation on the ability to heal through collective memory. Conroy followed My Losing Season with a culinary memoir, The Pat Conroy Cookbook (2004), a collection of recipes and reminiscences that was recently identified by the Paris Review as “one of the very best of the genre.”

his work. His memoir My Losing Season (2002) allowed Conroy to reconnect with teammates as he sought to recreate his final season on the Citadel basketball team, and the book functions, in part, as a meditation on the ability to heal through collective memory. Conroy followed My Losing Season with a culinary memoir, The Pat Conroy Cookbook (2004), a collection of recipes and reminiscences that was recently identified by the Paris Review as “one of the very best of the genre.”

Conroy’s fifth novel and ninth book, South of Broad (2009) uses James Joyce’s Ulysses as a loose model, and follows its aptly named protagonist, Leopold Bloom King, as he makes his way though Charleston and, later, San Francisco. Despite Conroy’s nod to Joyce, the novel is generally viewed as “quintessentially Conroy” in its fast-moving plotline and lyrical descriptions of Charleston. Just a year later, Conroy released My Reading Life (2010), a collection of essays that celebrate the books that have most influenced him, and tantalizingly offers fascinating glimpses into the daily life of a writer.

In 2013, Conroy published The Death of Santini. Subtitled “The Story of a Father and His Son,” the memoir details the impact that the publication of The Great Santini had on Conroy’s father, who, when faced with that novel’s portrait of him, underwent a radical reinvention, becoming a “kinder, gentler” Santini. In pulling the curtain aside and allowing readers to see Conroy as both protagonist and artist, The Death of Santini invites readers to think about the ways that life and art reverberate in each other in often invisible ways.

In 2014,Pat Conroy assumed the mantle of editor at large for Story River Books, his original southern fiction imprint at the University of South Carolina Press. Story River Press was launched in 2015.

Conroy was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in January 2016, and succumbed to the disease on March 4, 2016. He is buried in a small cemetery on St. Helena Island near the Penn Center, where as a teenager he first met Martin Luther King and where he was honored in 2011 for his dedication to social justice.

Conroy was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in January 2016, and succumbed to the disease on March 4, 2016. He is buried in a small cemetery on St. Helena Island near the Penn Center, where as a teenager he first met Martin Luther King and where he was honored in 2011 for his dedication to social justice.

In October of 2015, just months before his death, Conroy was feted by friends, family, readers, writers, and scholars at a three-day celebration of his work in honor of his 70th birthday. In his closing remarks, he told those gathered, “I have written [my] books because I thought if I explained my own life somehow, I could explain some of your life to you.” It is this impulse—to explore what it means to be human, and to recognize the ways each of us are connected in our search—that remains central to Conroy’s legacy.

(042518)