The Story Behind the Book

I kneeled in the snow, photographers and video cameramen orbiting around me, wondering who had done the far-too-realistic makeup for the faux thigh-bone fracture I was supposed to splint. Back at our tents, a Daily Show correspondent appeared and asked one of the local television reporters if observing the media boot camp had prepared her to cover the coverage of the war. Surreal is an overused word, but it was starting to seem appropriate.

Back home, it felt almost impolite to bring up the impending conflict amid the cheerful din in a bar in Washington’s Adams Morgan district. None of my friends wanted to hear about the war and everyone grew uncomfortable when I told them how unprepared I felt to administer First Aid to casualties. There was a long silence at the table until someone asked, “What happens if they start shooting at you?” I mustered up the toughest, meanest Cool-Hand-Luke face that I could and said, “I run.” Everyone laughed. I imagined what it would be like if a newspaper sent someone even less prepared than me into battle. I decided to abandon the novel I was working on and start taking notes.

Soon I was sitting on a folding chair on the Kuwait Hilton tennis courts, under palm trees tickled by the breeze off the Persian Gulf. It was a lovely day except for the fact that we were trying on our gas masks. One part summer camp and one part life-or-death educational seminar, each group of a dozen reporters had an Army sergeant acting as mother hen, trying to remain stern and serious while also making fun of our ineptitude.

There was just enough bootleg alcohol to fuel the hotel parties until Central Command deposited each of us with our respective military units. I, for one, had a moment of pathetic clarity when I dropped my bags in a porn-strewn tent in the desert, filled with foul-mouthed Marines who looked as ready to accept me among them as gang members are enthused about initiating a kindergarten teacher.

Just before the invasion began, we came under missile attack unexpectedly. Loudspeakers shouted “Code Red” as we rushed for the bunkers, pulling on our protective gear in mid-sprint. An attractive young lady from one of the morning talk shows had been interviewing Marines, asking them to record messages for the audience back home. I witnessed a hysterical breakdown for the first time in my life. In a sea of wisecracking grunts in gas masks this poor woman had none. She was crying and shaking and shrieking. I felt bad for her, but also thought to myself, “Jimmy Stephens, gossip columnist, reporting for duty.” He started to become my alter-ego. At each step the question was, “What would Jimmy do?”

Jimmy’s experience in the war is not my own. I was embedded with Marine attack helicopters, flying out of a base in Northern Kuwait. Jimmy’s Humvee ride to Baghdad is much closer to the experience of many of my friends and colleagues who were kind enough to provide technical support in the writing of the novel.

Within days of returning to Washington I had given notice at the Journal and begun working full-time on the book. With thousands of pages of firsthand reporting and access to many of the reporters who had been riding with infantry platoons, I found an abundance of material. There were lighter moments and darker ones. A friend lost his closest buddy over there near the end of the campaign.

My book would reflect the good and the bad. I wouldn’t show war as produced by Jerry Bruckheimer, with explosions and dramatic rescues at every turn. In the humdrum reality of war there are more people behind the action than on the front lines, complaining about the food, telling dirty jokes and, above all else, just waiting around. I had made friends with the Marines in my squadron. Behind the cursing, swaggering Cobra helicopter pilots and oil-stained mechanics were real guys I could relate to during midnight discussions under the desert stars. The humanity that never comes through in the canned quotes these men and women give you when the notebook is out or the camera is on was missing from the coverage of the war. I would tell that story. And the way that a person — gossip columnist at war or everyday Joe at a new job — deals with being into something way over his head, could say a lot about the human condition beyond just a few laughs.

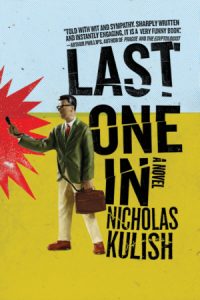

Photo by Sarah Shatz