The Story Behind the Book

And they stopped building the city.”

Genesis 11:10

“The universe is expanding!”

Alvy Singer, Annie Hall

When I was growing up in the small, Jewish enclave of West Rogers Park on the north side of Chicago, my universe, like that of most every child, was exceedingly small. A six-block hike to Ner Tamid Synagogue seemed a nearly impossible venture; one only crossed California Avenue with the aid of a police officer or patrol boy. Over time, my universe expanded, growing to encompass the city of Chicago, the state of Illinois, then America, and, when my fiancée was living in Germany, practically the entire world. Or so it seemed. But whenever I return to West Rogers Park to visit my parents, who still live in the same home they’ve owned for forty-three years, I suddenly feel the universe contracting again until it sometimes feels as if it’s no bigger than the one I knew as a child.

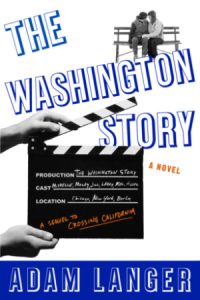

In writing The Washington Story, I have been consumed with this idea of an expanding and contracting notion of place, of the worlds that are contained within larger worlds. In my previous novel, Crossing California, I chose to study a very circumscribed location, that of West Rogers Park, and the borders that existed within it. With the new novel, I have decided to explore the world as it expands beyond this small neighborhood.

The Washington Story is set over a five-year period and the structure of the novel is inspired by the five books of Moses, which are also, in part, a story of Diaspora. The novel concerns assimilation, the place of the Jew within the expanding universe, the relationships between Jews and African-Americans, and those among conservative, orthodox, reconstructionist, and non-practicing Jews. It begins on November 10, 1982, when Harold Washington announces his candidacy to become the first black mayor of Chicago, and ends on November 24, 1987, the day of Mayor Washington’s untimely death. Between ’82 and ‘87, many events of historical significance took place—most notably, the twilight of the Soviet Union: the deaths of Leonid Brezhnev, Yuri Andropov, and Konstantin Chernenko, and the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev. But I most associate this era with Harold Washington, whom I dutifully researched as a 15-year-old Chicago Magazine intern in 1982. In the heart of the Reagan era, Washington represented a force for change and unity in times of race and class struggle, and was the flashpoint for a citywide controversy as Chicago debated between electing its first black mayor or its first Jewish mayor, Bernard Epton. The Washington Story is not a book about Harold Washington, Bernie Epton, nor any other historical figure or incident. It comprises five books about characters whose worlds are in the process of expanding or contracting, set against the historical backdrop of the mid-1980’s.

Book I (Eruv, or Jill and Muley’s Book of Boundaries), is set predominantly in West Rogers Park during Harold Washington’s contentious first campaign, when high school junior Jill Wasserstrom, a fifteen-year-old Maoist who donated all of her Bat Mitzvah money to charity, experiences two love affairs: one in her neighborhood with a young African-American and one beyond its borders with a lapsed Catholic. In Book II (Be-Midbar, or Mel and Michelle’s Book of Choices), the world expands to encompass the entire city of Chicago from October 1983 (when the south side White Sox lost the American League Championship Series) to October 1984 (when the north side Cubs lost the National League Championship Series). In this book, 19-year-old white actress Michelle Wasserstrom and 36-year-old black filmmaker Mel Coleman fall in love during the making of a gangster flick exploring the tension between Chicago’s north and south side underworlds. Book III (Shemot, or Jill and Becky’s Book of Exodus), concerns Jill Wasserstrom’s eventful freshman year of college as Jill leaves West Rogers Park behind to study in her late mother’s hometown of Poughkeepsie, New York, where she hopes to reunite with her grandmother whom she hasn’t seen in a decade, and where her roommate Bibi Eisenstadt becomes involved with a Gentile grad student. The boundaries in Book IV (Kaddish, or Muley and Hillel’s Book of Mourning) expand into the celestial realm, beginning in Chicago with the first appearance of Halley’s Comet in 76 years, journeying to Cape Canaveral, Florida, and ending with the first anniversary of the explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger; these events inspire film projects conceived by Art Institute student Muley Scott Wills who finds himself at odds with his hypochondriacal roommate Hillel Levy following a tragedy involving Muley’s father. In Book V (Aliyah, or Jill and Rachel’s Book of Homecoming), the expanding world begins to contract—from the heavens above to Europe, then finally back to Chicago, where five-year-old Rachel Wasserstrom waits in vain for her sister to return home from Germany for the family’s last Thanksgiving in West Rogers Park, thus completing the cycle.

I distinctly remember the evening of November 24, 1987. I was sitting in the backseat of my girlfriend’s father’s car; he was driving us to Hartford, Connecticut, where I would celebrate my first Thanksgiving outside of Chicago, my first with a non-Jewish family. We were on a dark stretch of highway and we had been listening to a song by Joe Jackson from the album Night and Day when the news came on: Harold Washington had died of a heart attack at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. I remembered having heard about other tragedies—in 1976, when Mayor Daley died, I was in my parents’ den, watching the movie How to Steal a Million; in 1980, I was in my childhood bedroom when my mother woke me to tell me John Lennon had been shot. This time, in 1987, it felt strange that I was no longer in a safe, familiar place seemingly protected from the events of the outside world, that I was no longer home, But then again, my definition of home was changing—my universe had expanded, for better and for worse.